Exhibited Works

Informations

Barthélémy Toguo

The missing part

12.01.23 - 04.03.23

Opening on Thursday, January 12th, 18:00

In presence of the artist

Barthélémy Toguo, humanism & altruism

Entitled "The missing part", the exhibition presented by Nosbaum Reding follows on from the retrospective devoted to Barthélémy Toguo by the Villa Merkel in Esslingen (Germany) from August to October 2022. It brings together a group of works that illustrates the polymorphic approach of the artist and acknowledges the primordial place he occupies both within African art and on the international scene.

For nearly thirty years, Toguo has demonstrated an exemplary humanist commitment, establishing himself as the spokesperson for an African identity that claims its independence from the Western world. A fighter from the outset to ensure that African art is not taken hostage, he has never wavered in his quasi-militant activity to promote it throughout the world, while at the same time ensuring that Africans in the diaspora who have skills in all creative pursuits pass them on to their fellow Africans.

To this end and with his own funds, Barthélémy Toguo has created an astonishing complex in Bandjoun Station, Cameroon, consisting of a museum, a collection and residences for artists and intellectuals, coupled with a significant agricultural activity. Exhibitions, meetings, debates and educational projects are all part of the programme to raise awareness and help Africans take charge of their own future. Buoyed by the inertia of the Cameroonian state to engage in all forms of cultural action, the artist decided to launch a new project to build a contemporary art museum in Yaounde that was also a place for symposiums and theoretical reflection on creativity, thereby combining all disciplines.

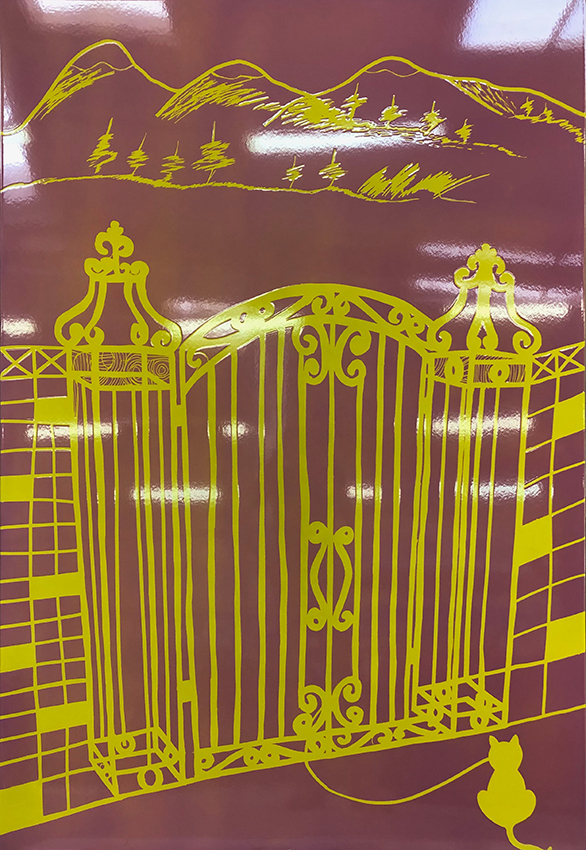

The title of his exhibition - "The missing part" - refers to the idea of that something which has been forgotten or which has been marginalized by the passage of time but is nevertheless necessary for any creative intention. A missing part that must be recalled, reactivated, brought back to oneself in order to nourish the spirit and better be able to share with the other.

Interview with the artist

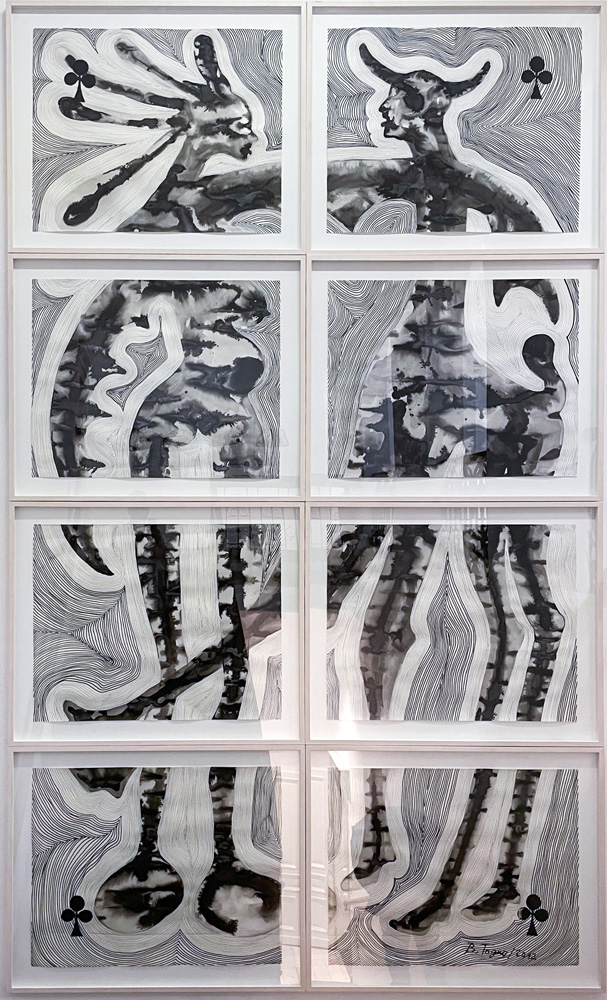

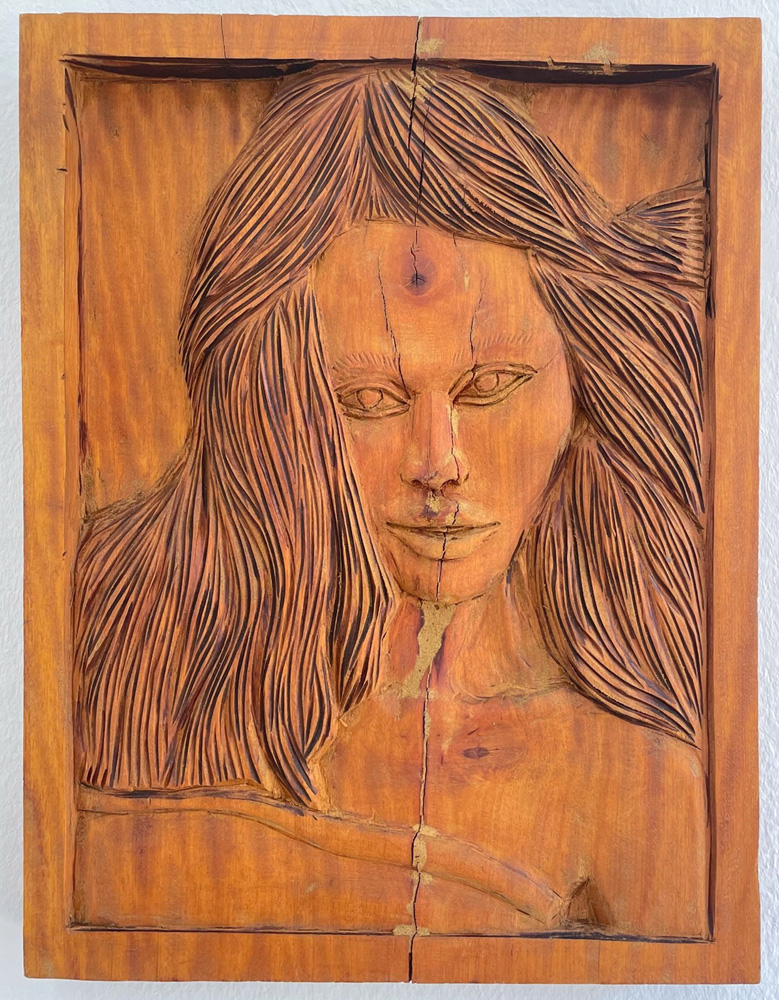

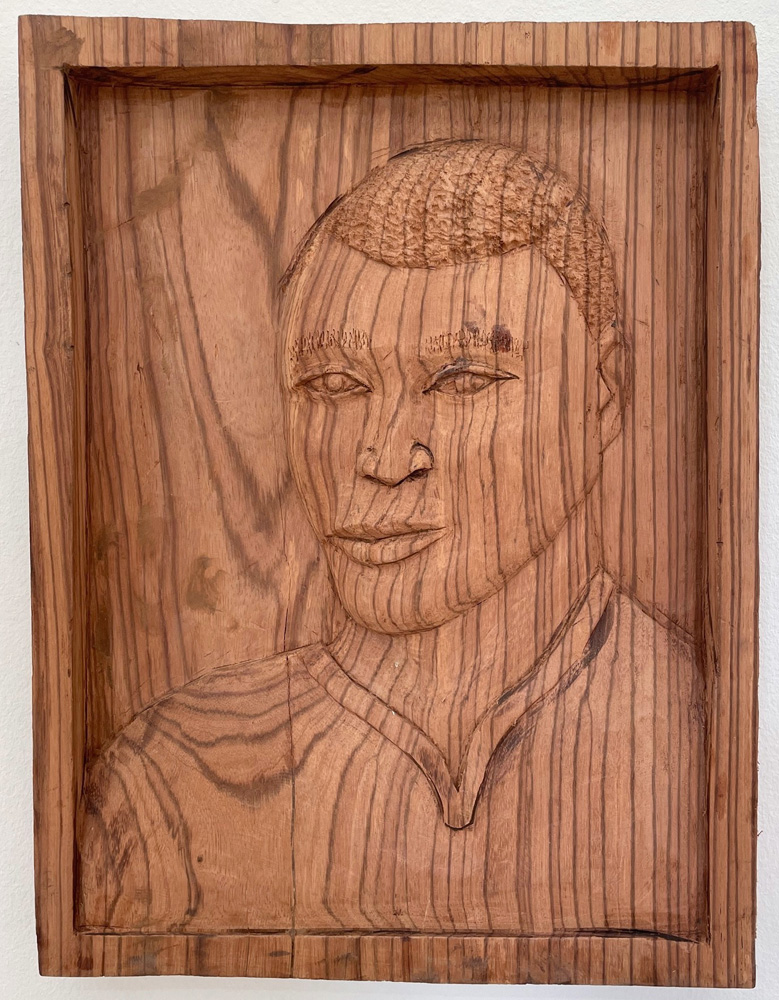

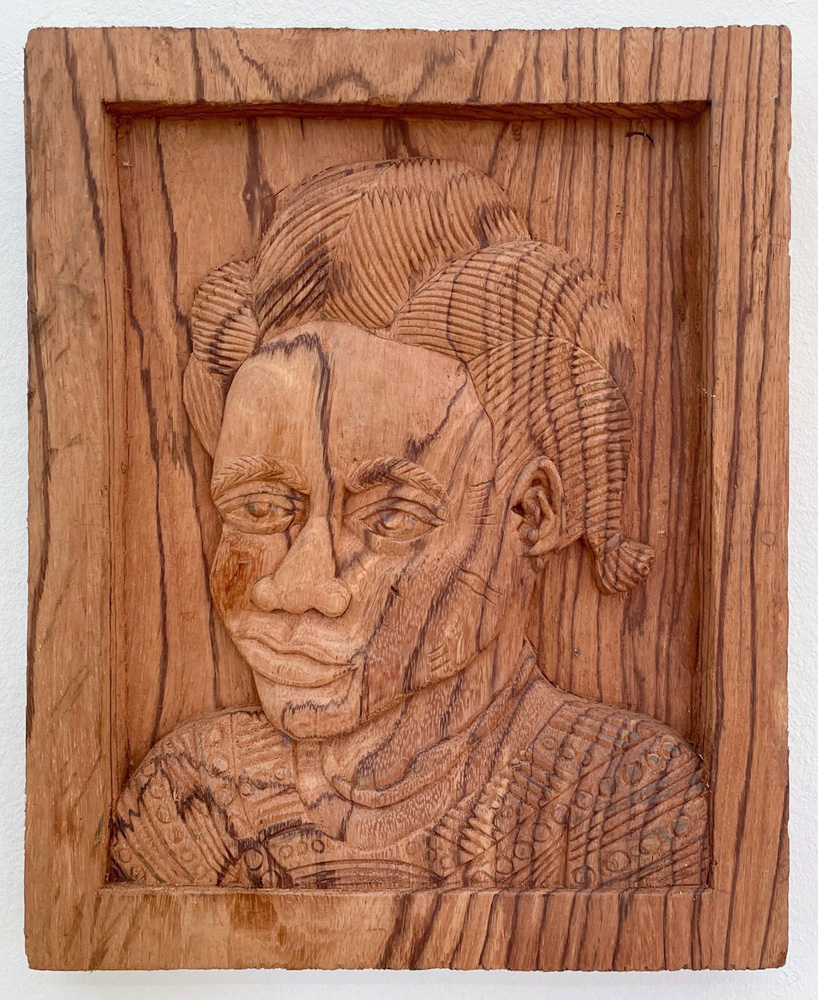

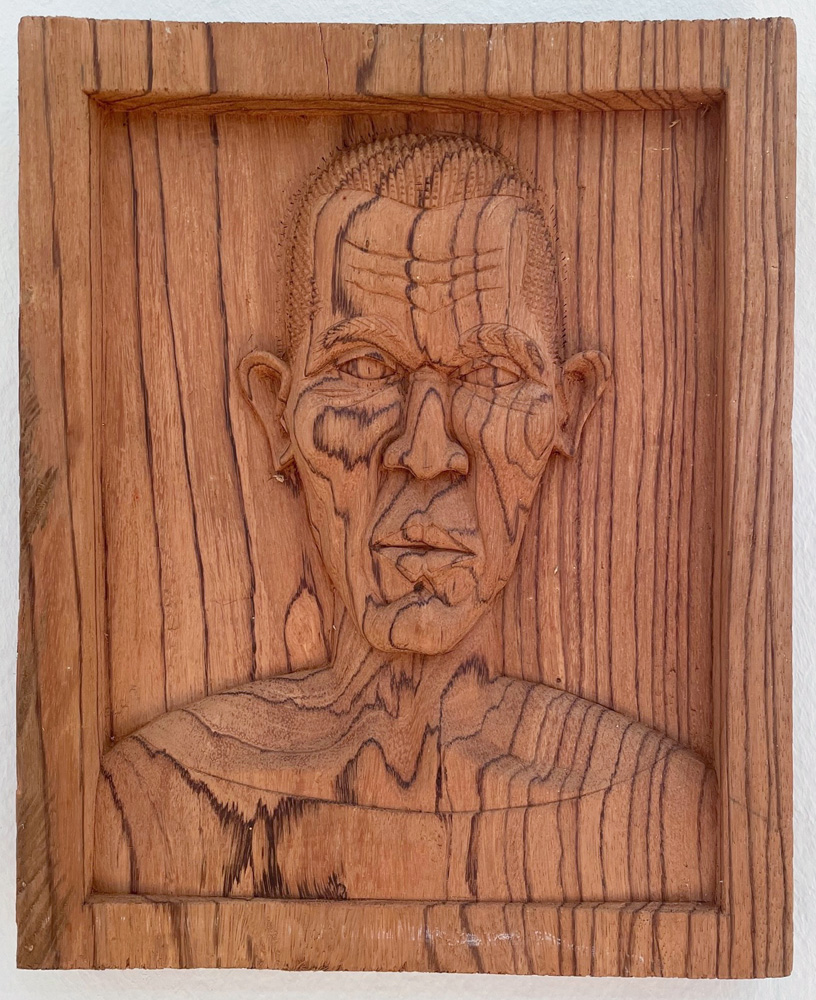

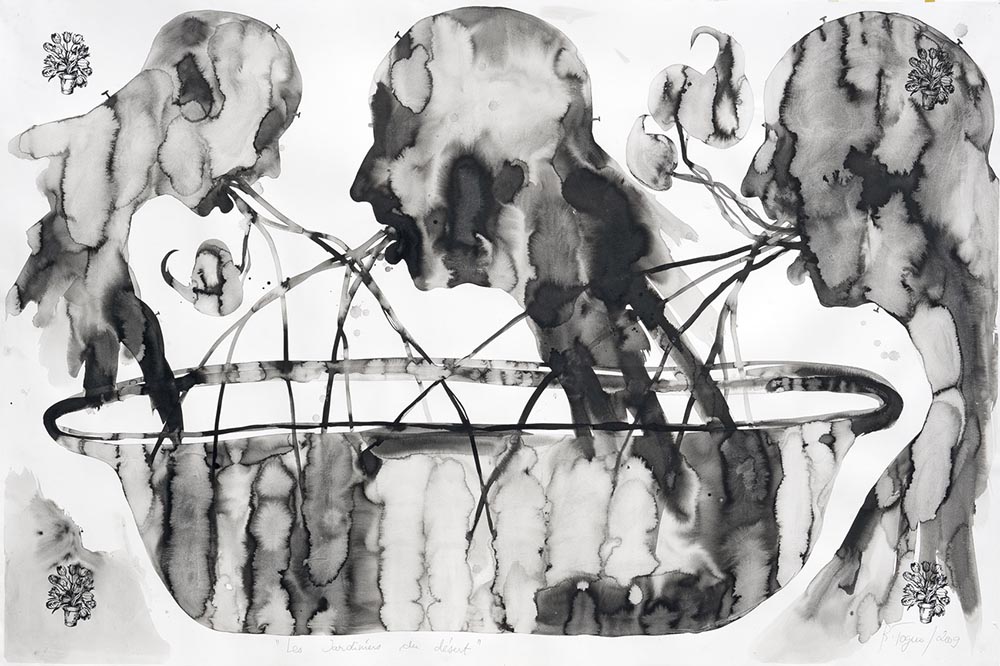

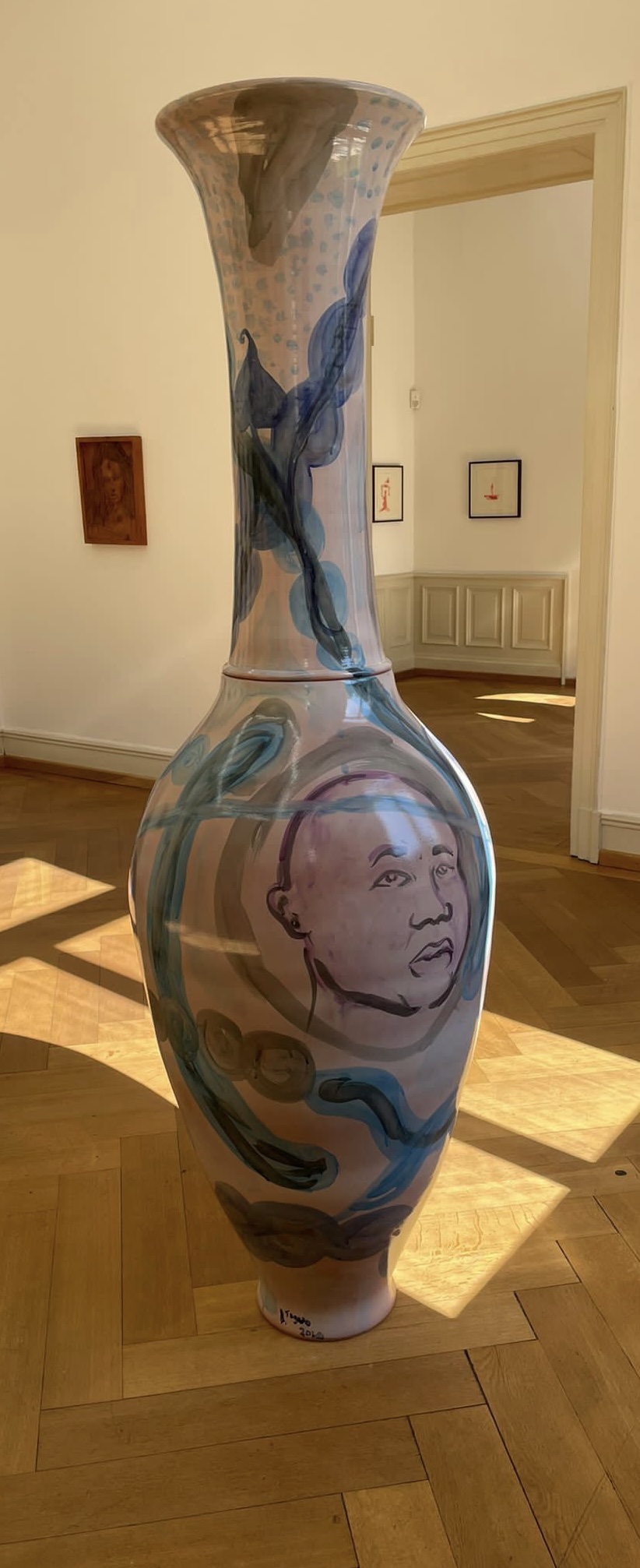

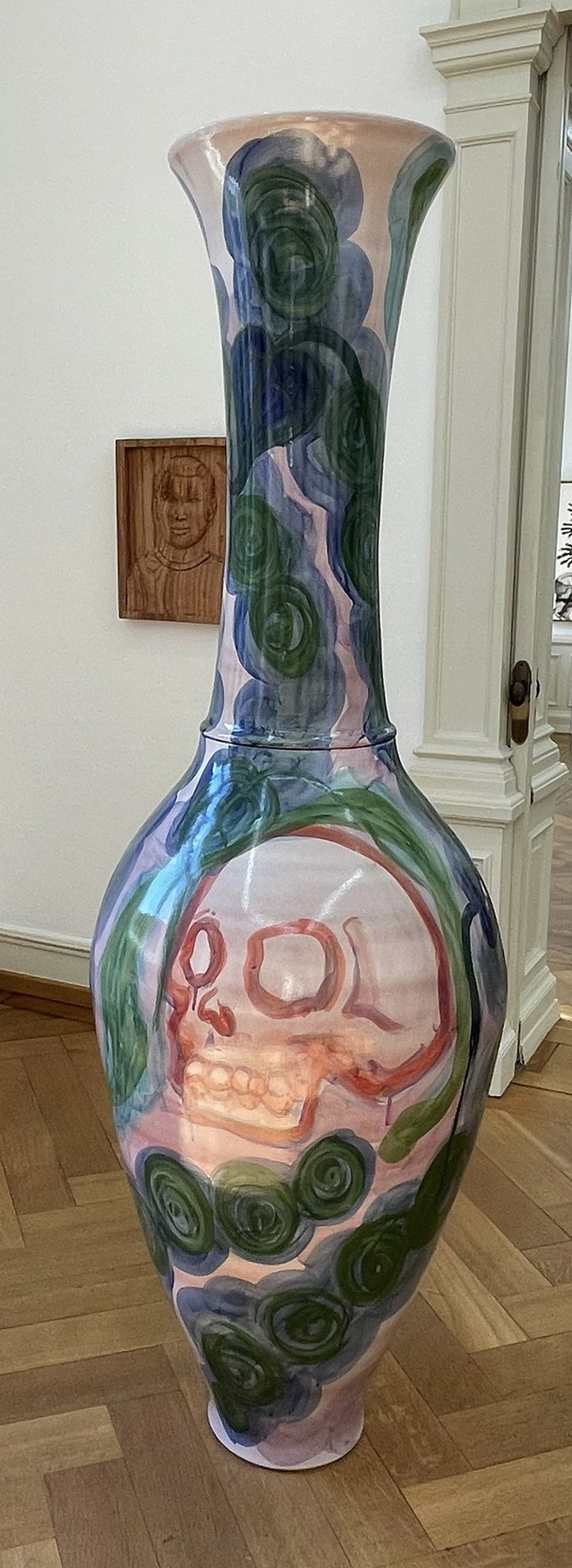

Whatever medium you work in - drawing, painting, ceramics, sculpture, etc.- the human figure is omnipresent in your art. What meaning should we attribute to this recurrence?

It is a universal figure that does not belong to any race - neither yellow, nor red, nor black, nor white. It has no nationality or gender. It is a figure, the archetype of the human body. It is symbolic of an affected state of the human being – at times suffering, at times fulfilled, at others worried, or rebellious.

They are often fragments of the body: hands, heads, arms... What does this relate to?

It all depends on what I want to express, or what is going through my mind at the very moment I am working. There is no preamble, I am an artist who operates empirically. Sometimes the figure even takes on a hybrid form, half human, half animal.

Where do these figures come from? From what cultural background?

They are not linked to any particular culture. These figures belong to me, fully. They are my creations. They come from my imagination, from a mythology that is very personal to me. They are phantasmatic figures to whom I give all sorts of attributes. One of them makes a flower grow out of its mouth while another, lying on the ground, sees the ends of its hands and feet transformed into branches: they do not refer to any pre-existing model.

What motivates you in such creations?

The celebration of the living. For me, to celebrate is to honour. These drawings are about honouring life. The hands are about solidarity. It is the symbol of what can give and receive at the same time.

What nourishes your universe?

It is the human being in its most general sense. The one I see during all my travels in the many trips I make for my work. I am a very observant person. I read newspapers, I watch TV, I am constantly informed about the world. My imagination is constantly fed by what I experience and what I see on a daily basis. As I am always on the move - one day in Sao Paulo, the next in Lisbon, the day after that in Asia - I glean from here and there everything that surrounds me. I am a bulimic of the world. At the very beginning of my life as an artist, I lived for four years in Abidjan, four years in Grenoble, two years in Düsseldorf, then two years in Paris. Today, I come and go between the capital and Cameroon.

And all this comes out in your work in one way or another…

Absolutely, but never on an anecdotal level; my images never seek to illustrate a particular situation that I have experienced, but what I feel. I'm not an artist who fills sketchbooks with the different situations he goes through, instead I gather all sorts of perceptions and sensations deep inside me. At work, I am governed by a kind of commemorative sensibility.

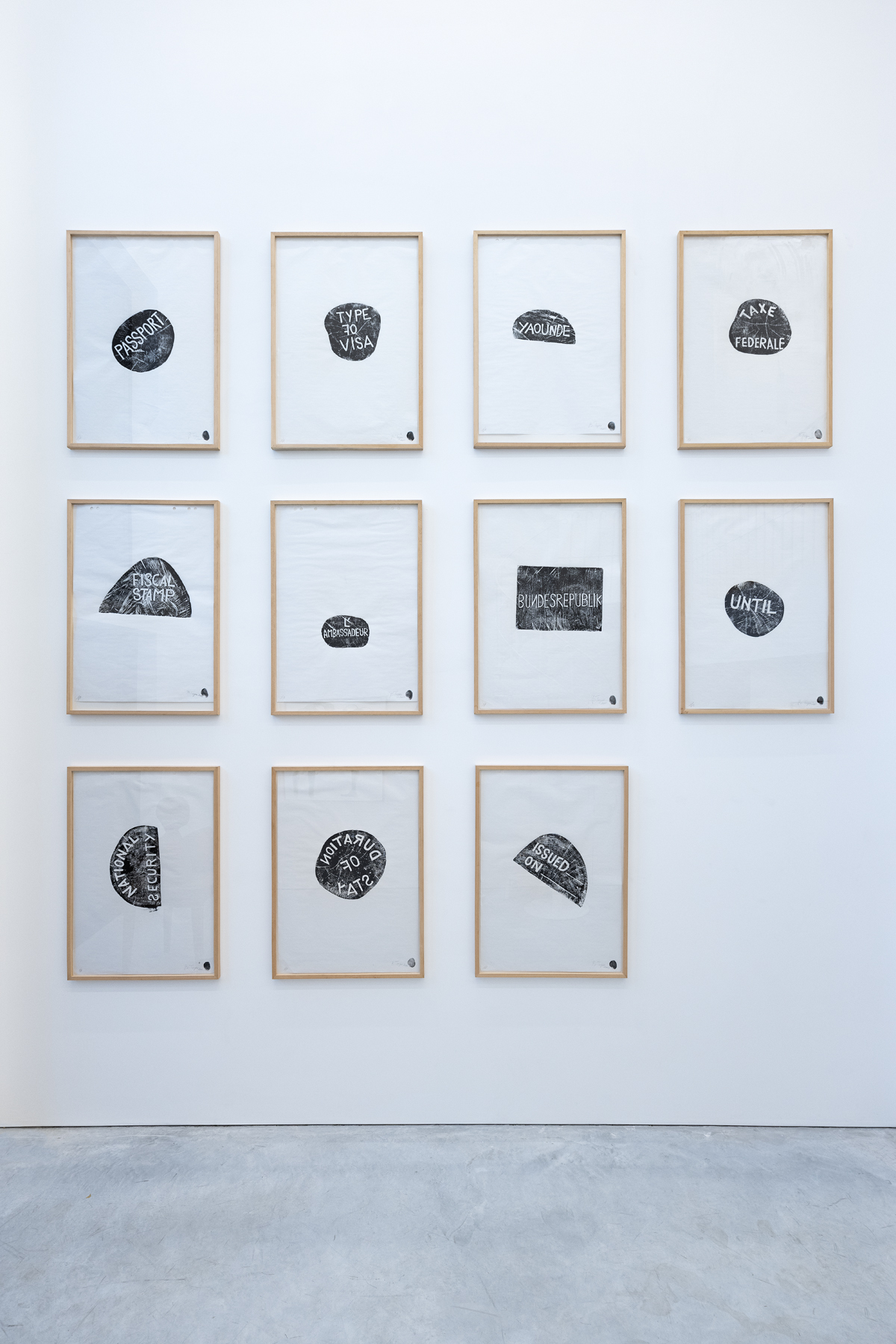

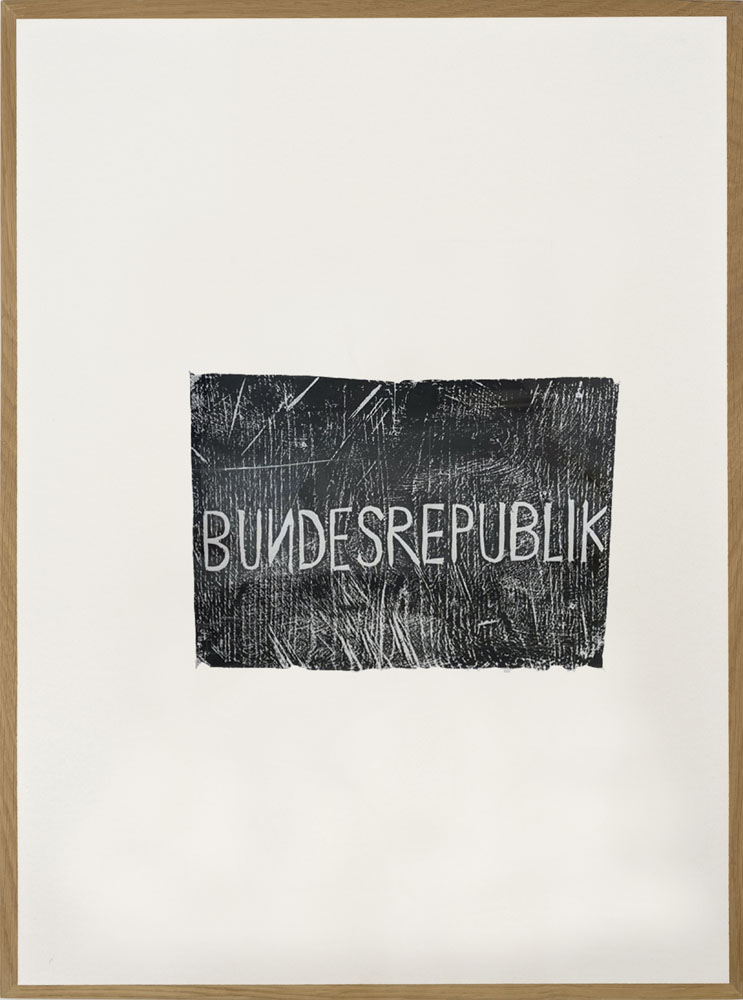

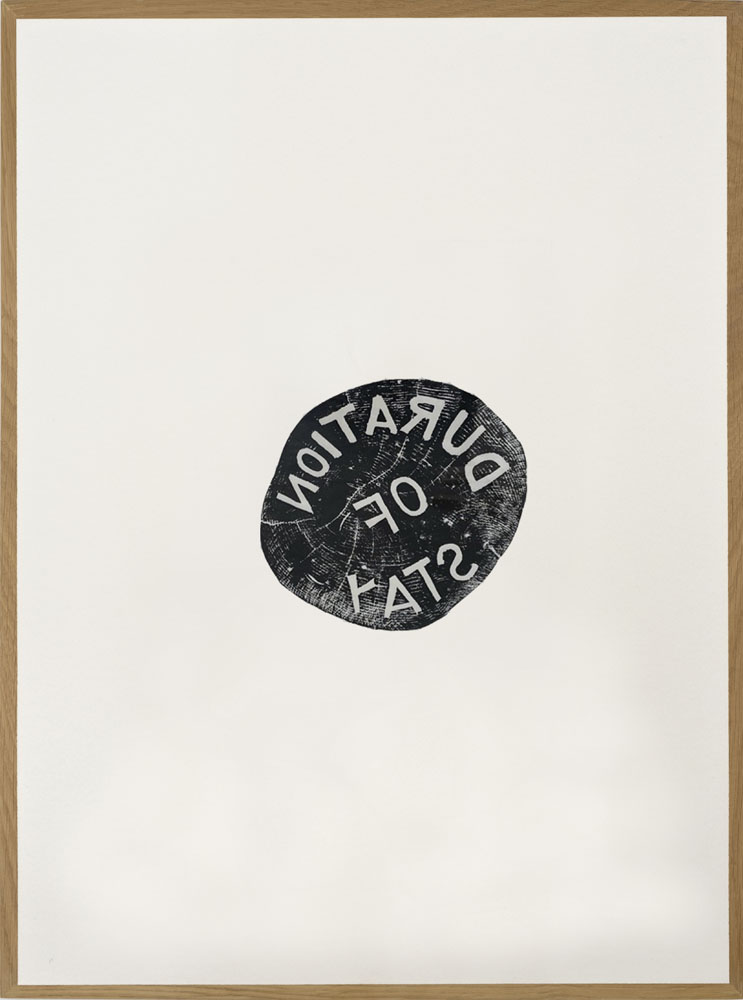

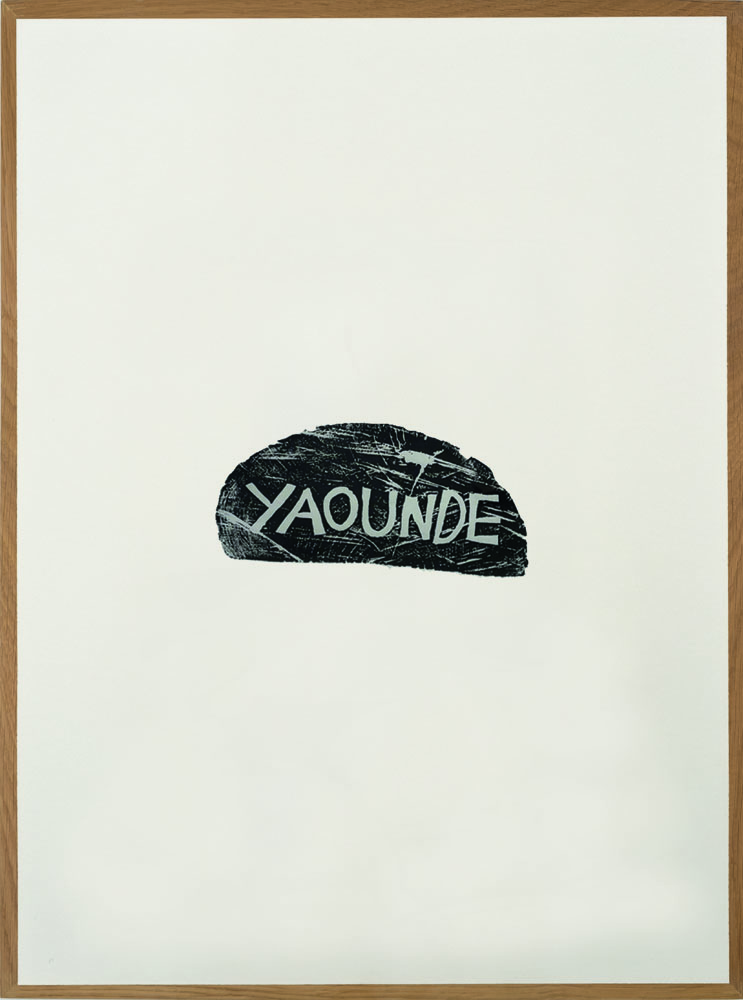

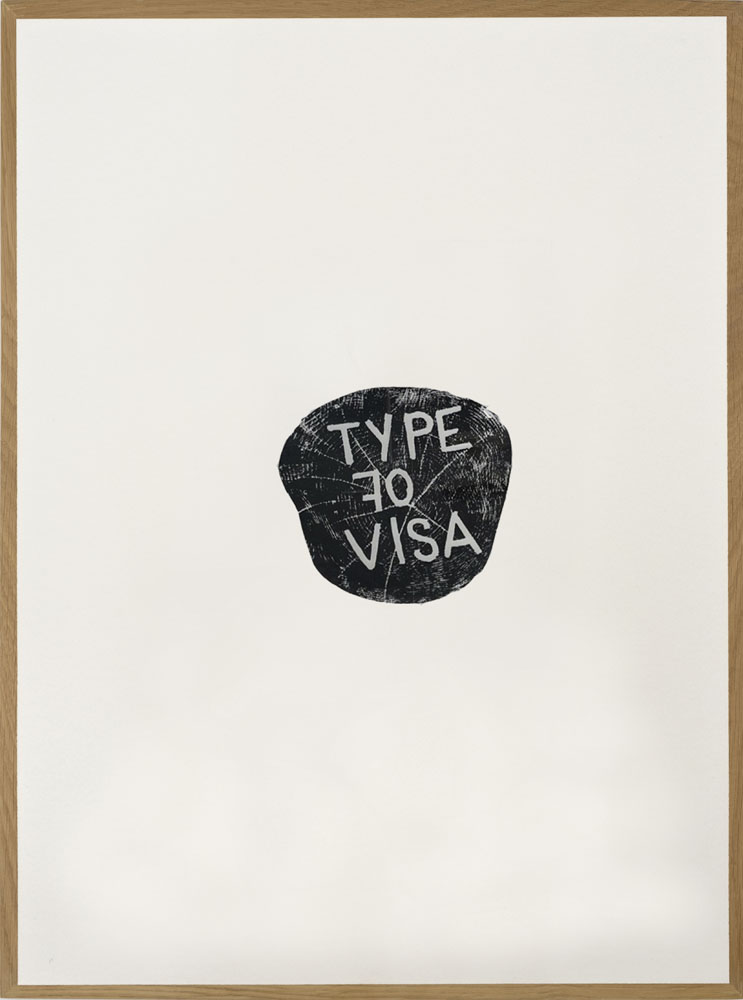

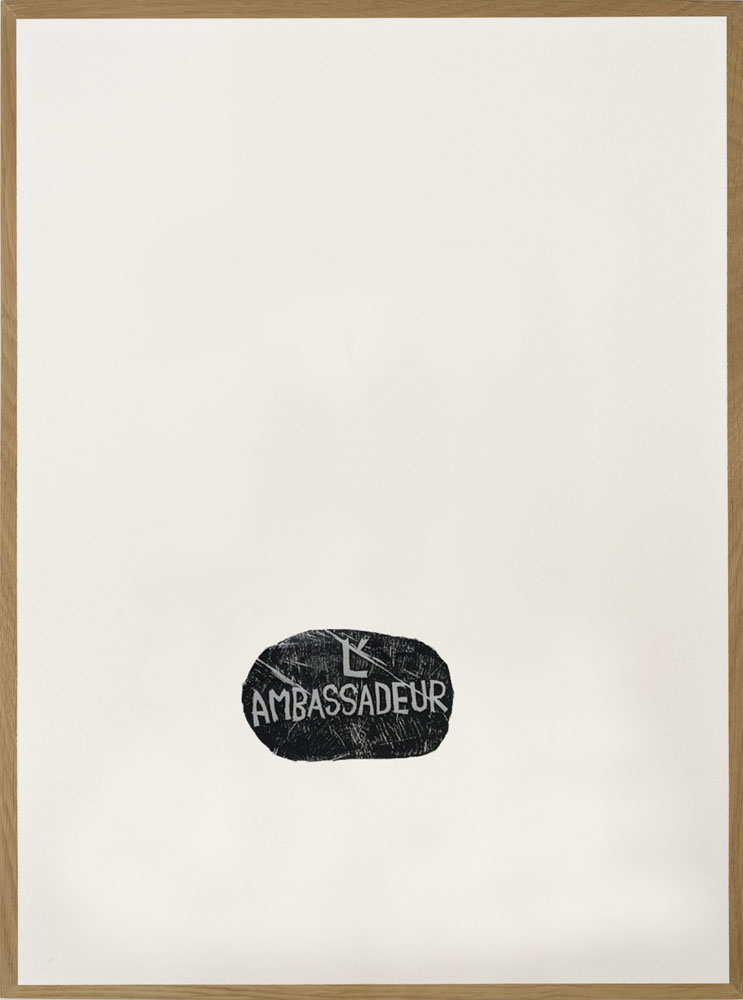

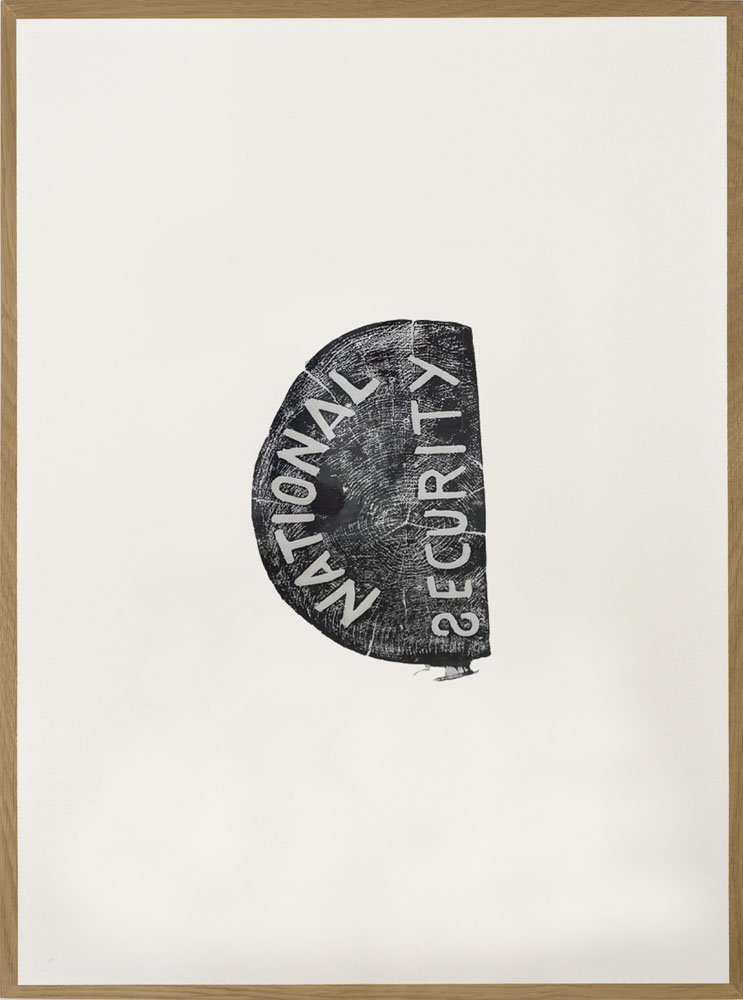

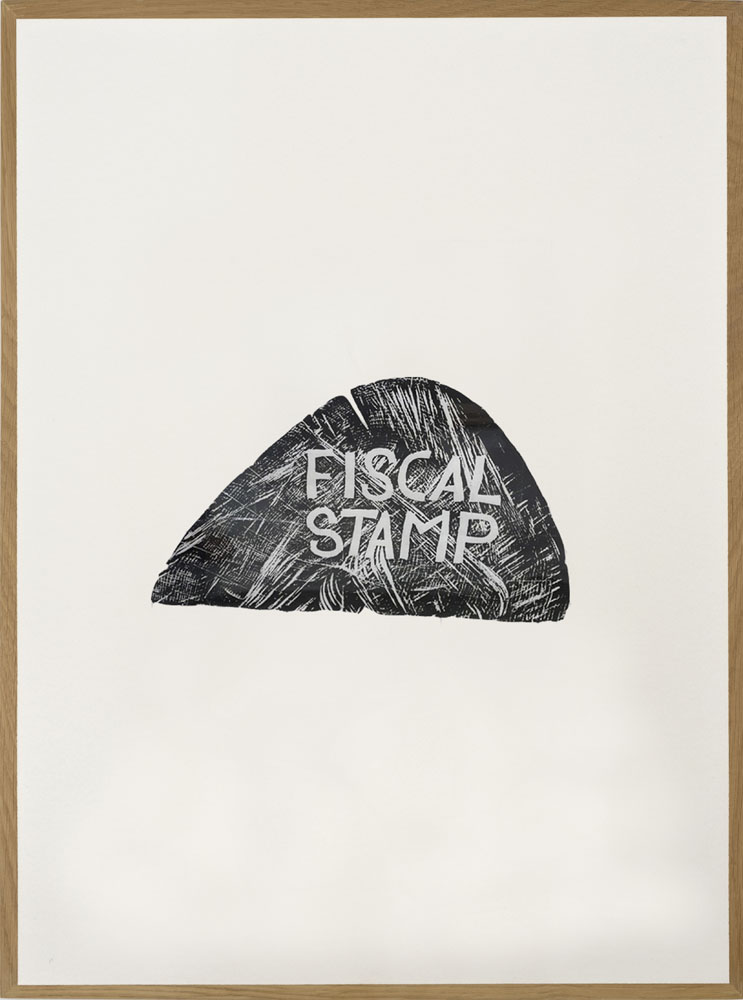

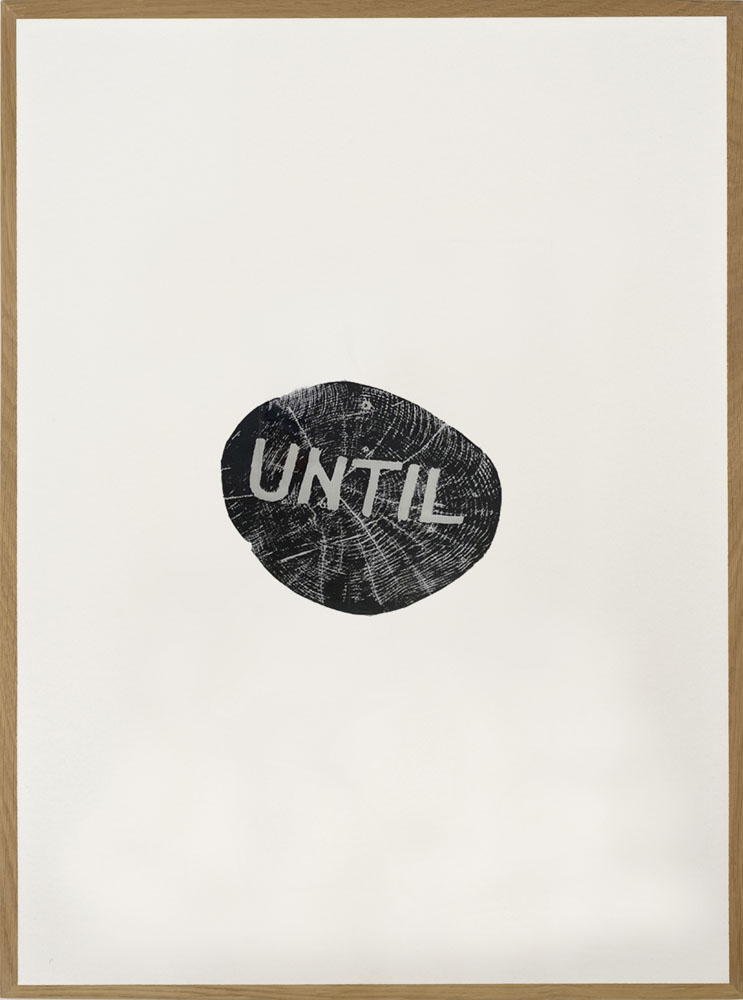

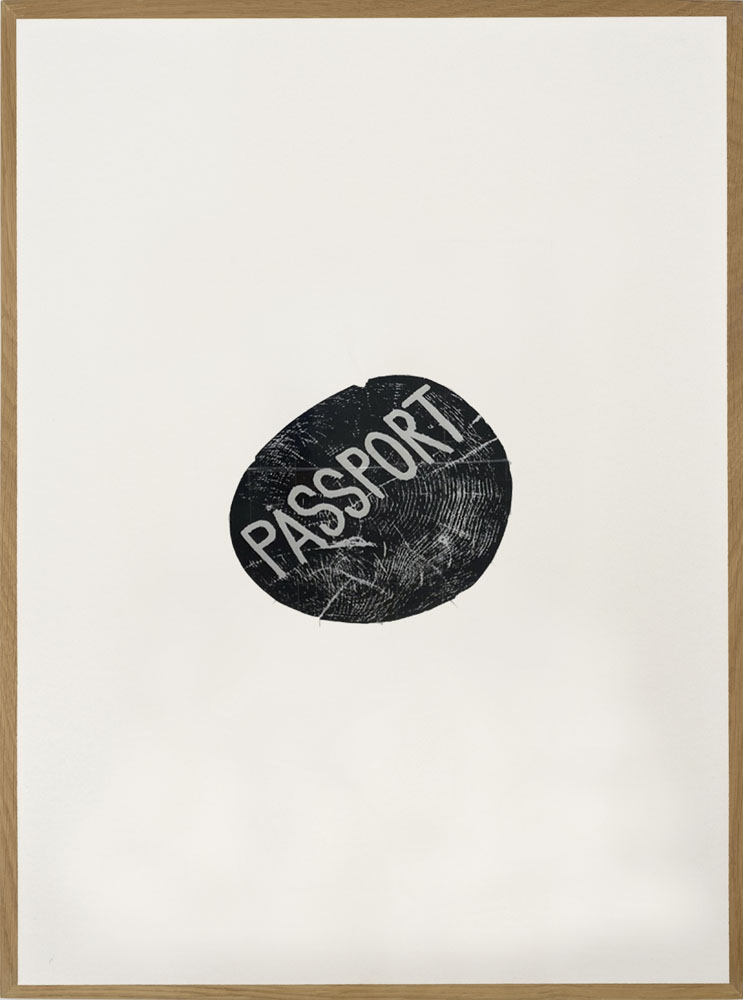

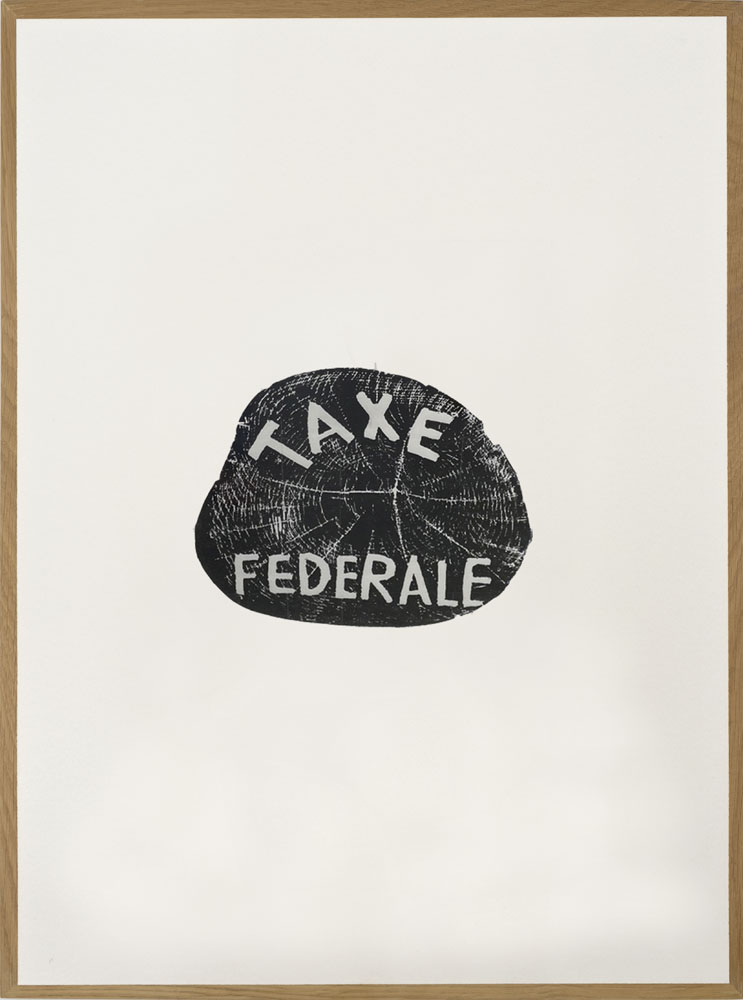

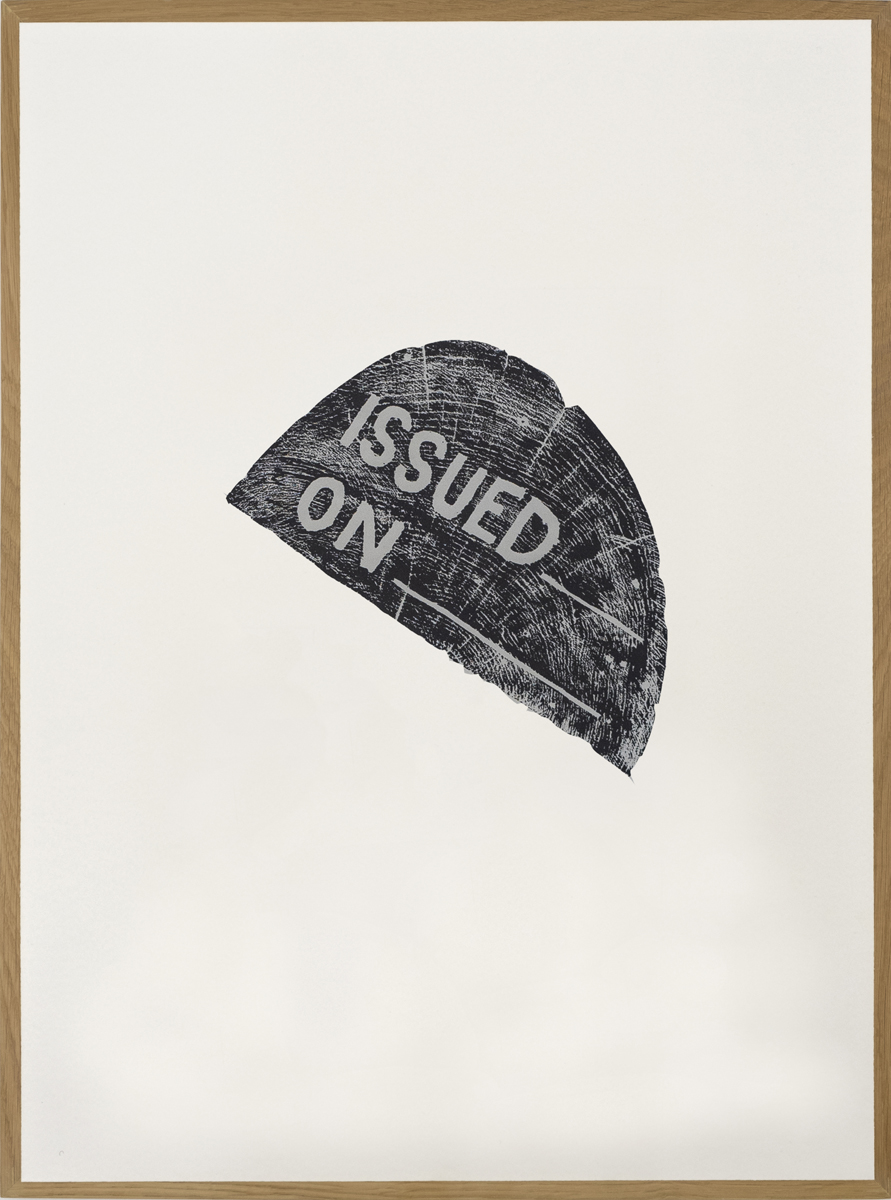

The fact remains that there is always an origin to everything. How did the idea of the wooden stamps you use to print words and sayings that are like manifestos come about, for example?

Originally, it was the memory of a bus I had seen that displayed slogans written by young Africans as a way of protesting. I write words that refer to stories of suffering and constraint as well as social facts. They are indeed manifest works, political in nature.

In the way you have conceived certain works, it is possible to see various and varied installations where the printed words appear as cries. What is the function of the artist for you? If not, what role do you consider yourself to have as an artist?

The role I want to play through my work is to accompany people who are going through difficult times - if need be, to cry with them about their difficulties, like the mourners of old. Exile, migration, the fraudulent circulation of trade, North-South inequalities, epidemics and pandemics, these are all issues that I have tackled because I keep coming across them, living them, experiencing them as I travel. It is impossible for me not to react. I have always subscribed to the thinking of Albert Camus who proclaimed the need to go towards those who are in difficulties, to help them do something that will help them get out of their situation. It is a simple question of humanity.

- Phillipe Piguet -

Caption:

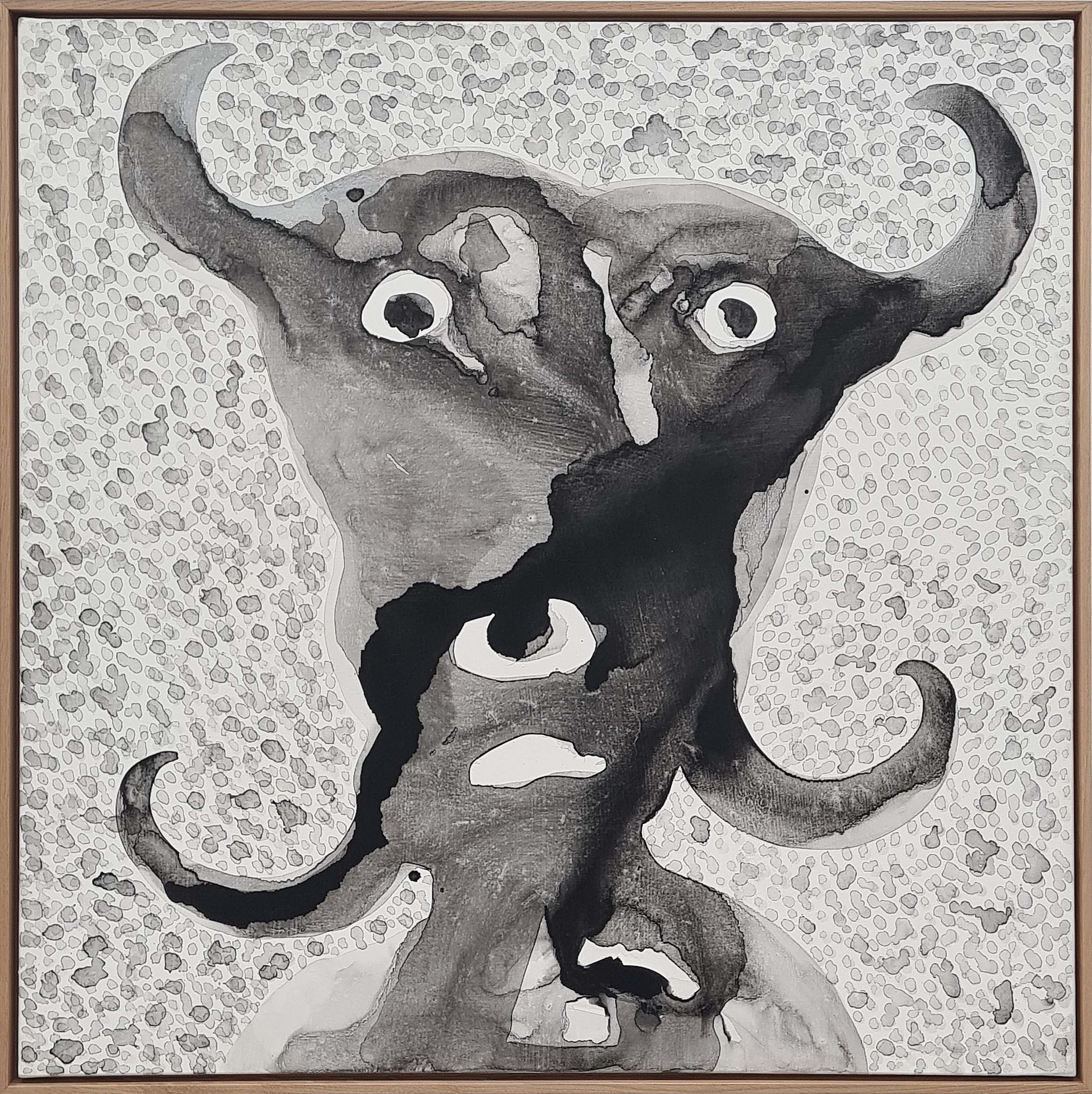

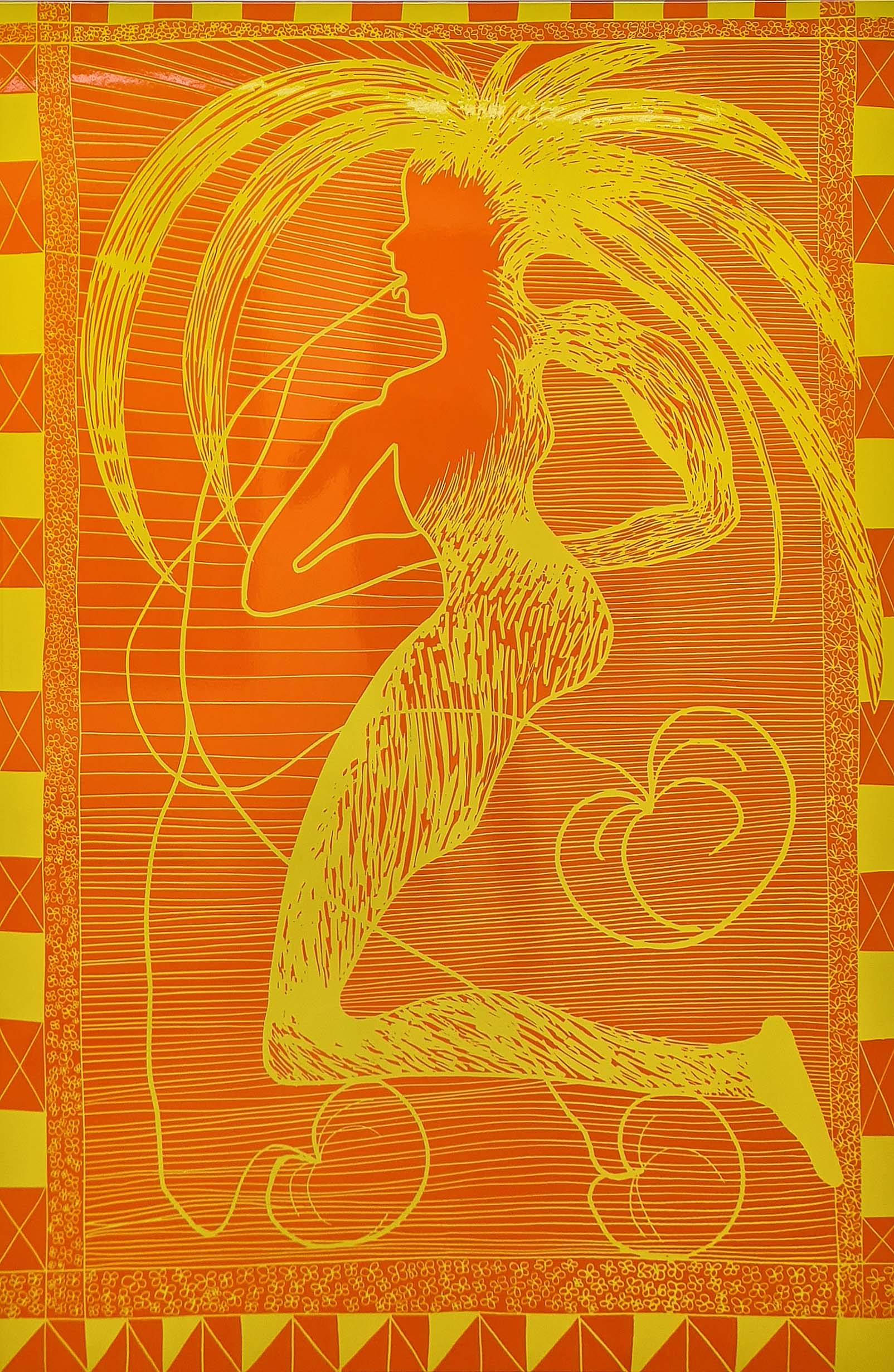

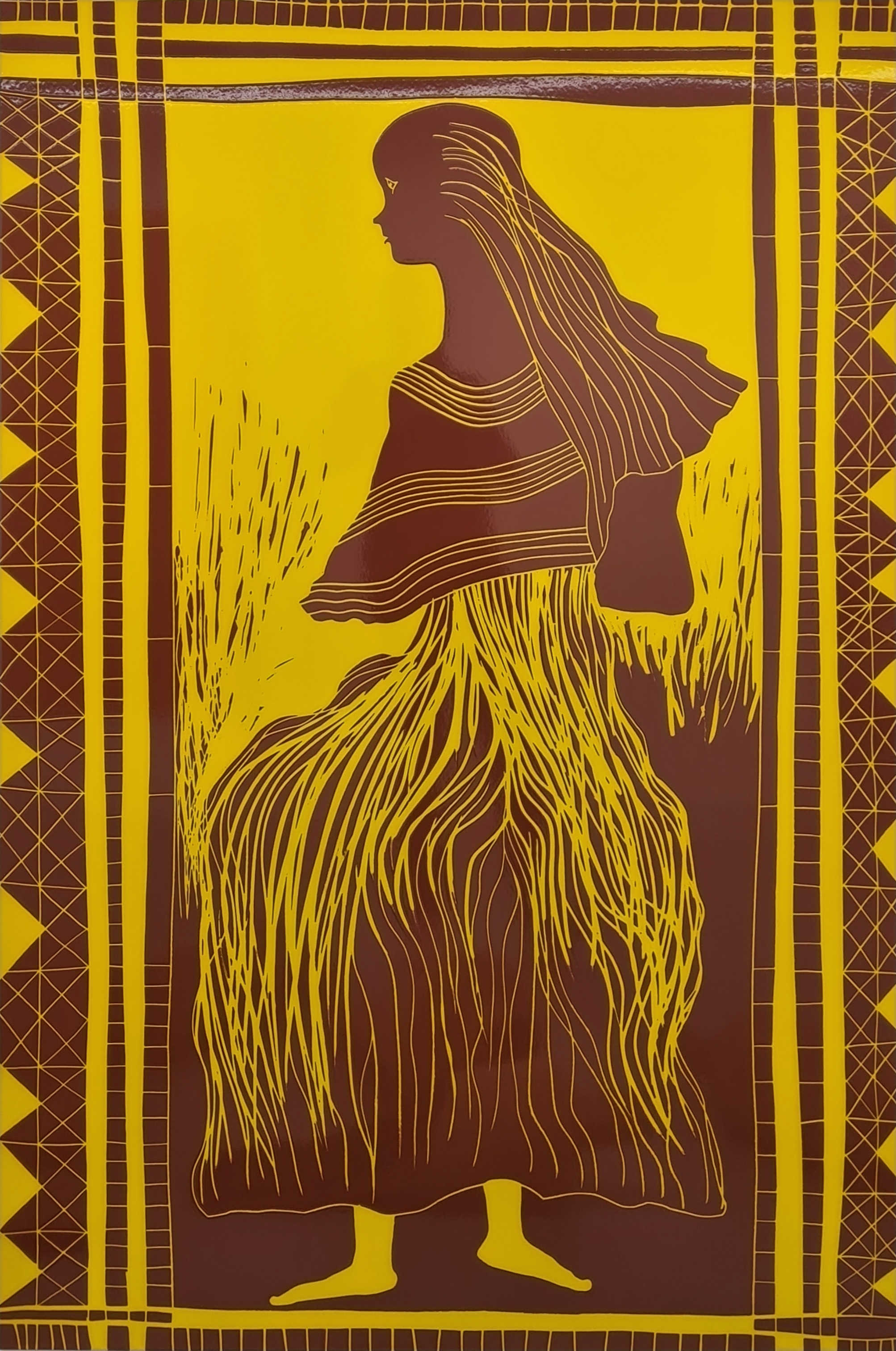

Barthélémy Toguo

Porte du bonheur, 2022

Ink on canvas

200 x 200 cm

Image: Villa Merkel

FR

Barthélémy Toguo

The missing part

12.01.23 - 04.03.23

Vernissage le jeudi 12 janvier à partir de 18h.

En présence de l'artiste

Barthélémy Toguo, humanisme & altruisme

Intitulée « The missing part », l’exposition présentée par Nosbaum Reding fait suite à la rétrospective que la Villa Merkel d’Esslingen (Allemagne) a consacrée à Barthélémy Toguo d’août à octobre 2022. Elle rassemble un ensemble d’oeuvres qui illustre la démarche polymorphe de l’artiste et acte la place primordiale qu’il occupe tant au sein de l’art africain que de la scène internationale.

Depuis près de trente ans qu’il est au travail, Toguo n’a cessé de témoigner d’un engagement humaniste exemplaire, s’imposant comme le porte-parole d’une identité africaine qui revendique son indépendance face au monde occidental. Combattant de la première heure pour que l’art africain ne soit pas pris en otage, il ne cesse de mener une activité quasi militante pour le faire connaître à travers le monde tout en s’appliquant à ce que les Africains de la diaspora qui ont des compétences dans tous les domaines de la création les transmettent à leurs semblables, en Afrique même.

A cet effet, avec ses fonds propres, Barthélémy Toguo a créé au Cameroun, à Bandjoun Station, un étonnant complexe fait d’un musée, d’une collection et de résidences d’artistes et d’intellectuels, doublé d’une importante activité agricole. Expositions, rencontres, débats, projets éducatifs sont au programme d’une dynamique d’éveil de la conscience et de prise en charge par les Africains eux-mêmes de leur avenir. Face à l’inertie de l’Etat camerounais d’engager toute forme d’action culturelle, l’artiste a décidé de lancer un nouveau projet de construction d’un musée d’art contemporain à Yaoundé, pour en faire notamment un lieu de symposium et de réflexion théorique à propos de création, toutes disciplines confondues.

Le titre de son exposition - « The missing part » - renvoie à l’idée de « part manquante », ce quelque chose que l’on a oublié ou que le temps a laissé de côté et qui est cependant nécessaire à toute intention créatrice. Part manquante qu’il faut donc rappeler, réactiver, ramener à soi de sorte à nourrir l’esprit pour mieux partager avec l’autre.

Interview avec l'artiste

Quel que soit le type d’œuvre - dessin, peinture, céramique, sculpture, etc. – que vous réalisez, la figure humaine est omniprésente dans votre travail. Quelle sens doit-on prêter à cette récurrence ?

C’est une figureuniversellequi n’appartient à aucune race - ni jaune, ni rouge, ni noire, ni blanche. Elle n’a ni nationalité, ni genre. C’est une silhouette, l’archétype du corps humain. Elle est symbolique d’un état affecté de l’être humain – tantôt souffrante, tantôt épanouie, tantôt inquiète, tantôt rebelle.

Ce sont souvent des fragments de corps : des mains, des têtes, des bras... A quoi cela correspond-il ?

Tout dépend de ce que je veux exprimer, de ce qui me traverse dans la tête au moment même où je travaille. Il n’y a pas de préambule, je suis un artiste qui opère de manière empirique. Parfois, la figure prend même une forme hybride, mi-humaine, mi-animale.

D’où proviennent donc ces figures ? De quel fonds culturel ?

Elles ne sont à rattacher à aucune culture particulière. Ces figures m’appartiennent, pleinement. Ce sont mes créations. Elles procèdent de mon imaginaire, d’une mythologie qui m’est très personnelle. Ce sont des figures fantasmatiques auxquelles j’accorde toutes sortes d’attributs. L’une fait sortir de sa bouche une fleur tandis qu’une autre, couchée au sol, voit transformées en ramures les extrémités de ses mains et de ses pieds : elles ne réfèrent en fit à aucun modèle préexistant.

Qu’est-ce qui motive en vous de telles créations ?

La célébration du vivant. Pour moi, célébrer, c’est honorer. Ces dessins visent à honorer la vie. Les mains, c’est la solidarité. C’est le symbole de ce qui peut tout à la fois donner et recevoir.

Qu’est-ce qui nourrit votre univers ?

C’est l’être humain dans sa plus grande généralité. Celui que je vois au cours de tous mes déplacements, des très nombreux voyages que je fais pour mon travail. Je suis quelqu’un de très observateur. Je lis les journaux, je regarde la télé, je m’informe du monde en permanence. Mon imaginaire ne cesse de se nourrir de ce que je vis et de ce que je vois au quotidien. Comme je suis toujours en mouvement - un jour à Sao Paulo, le lendemain à Lisbonne, le surlendemain en Asie -, je glane ici et là tout ce qui m’environne. Je suis un boulimique du monde. Au tout début de ma vie d’artiste, j’ai vécu quatre ans à Abidjan, quatre ans à Grenoble, deux ans à Düsseldorf, puis deux ans à Paris. Aujourd’hui, je vais et je viens entre la capitale et le Cameroun.

Et tout cela ressort dans votre travail d’une manière ou d’une autre...

Absolument, mais jamais sur un plan anecdotique ; mes images ne cherchent jamais à illustrer telle ou telle situation que je vis, mais ce que j’ai ressenti. Je ne suis pas un artiste qui remplis des cahiers de croquis des différentes situations qu’il traverse mais j’engrange au fond de moi toutes sortes de perceptions et de sensations. Au travail, c’est une forme d’écho mémoriel et sensible qui me gouverne.

Il n’en reste pas moins qu’il y a toujours une origine à toute chose. Comment est advenue, par exemple, l’idée de ces tampons de bois que vous utilisez à imprimer des mots et des paroles qui sont comme des manifestes ?

A l’origine, c’est le souvenir d’un bus qui affichait des slogans rédigés par de jeunes africains en guise de revendication. Moi, j’y inscris des mots qui renvoient aussi bien à des histoires de souffrance et de contrainte que de faits de société. Ce sont en effet des œuvres manifestes, à caractère politique.

Tel que vous avez conçu ce travail, il s’offre à voir dans des installations diverses et variées où les mots imprimés paraissent comme des cris. Quelle est pour vous la fonction de l’artiste ? Sinon quel rôle considérez-vous avoir en tant que tel ?

Le rôle que je veux jouer avec mon travail, c’est d’accompagner les gens qui traversent des moments difficiles - si besoin de pleurer de leurs difficultés avec eux, comme les pleureuses du temps jadis. L’exil, la question migratoire, la circulation frauduleuse des commerces, les inégalités Nord-Sud, les épi- et les pandémies, ce sont là toutes sortes de problématiques que j’ai abordées parce que je ne cesse de les croiser, de les vivre, de les éprouver au fil du temps et de mes déplacements. Il m’est impossible de rester sans réagir. J’ai toujours adhéré à la pensée d’Albert Camus qui proclamait la nécessité d’aller vers ceux qui sont dans des difficultés, de les aider à faire quelque chose pour les en sortir. C’est une simple question d’humanité

- Philippe Piguet -

Légende :

Barthélémy Toguo

Porte du bonheur, 2022

Encre sur toile

200 x 200 cm

Image: Villa Merkel