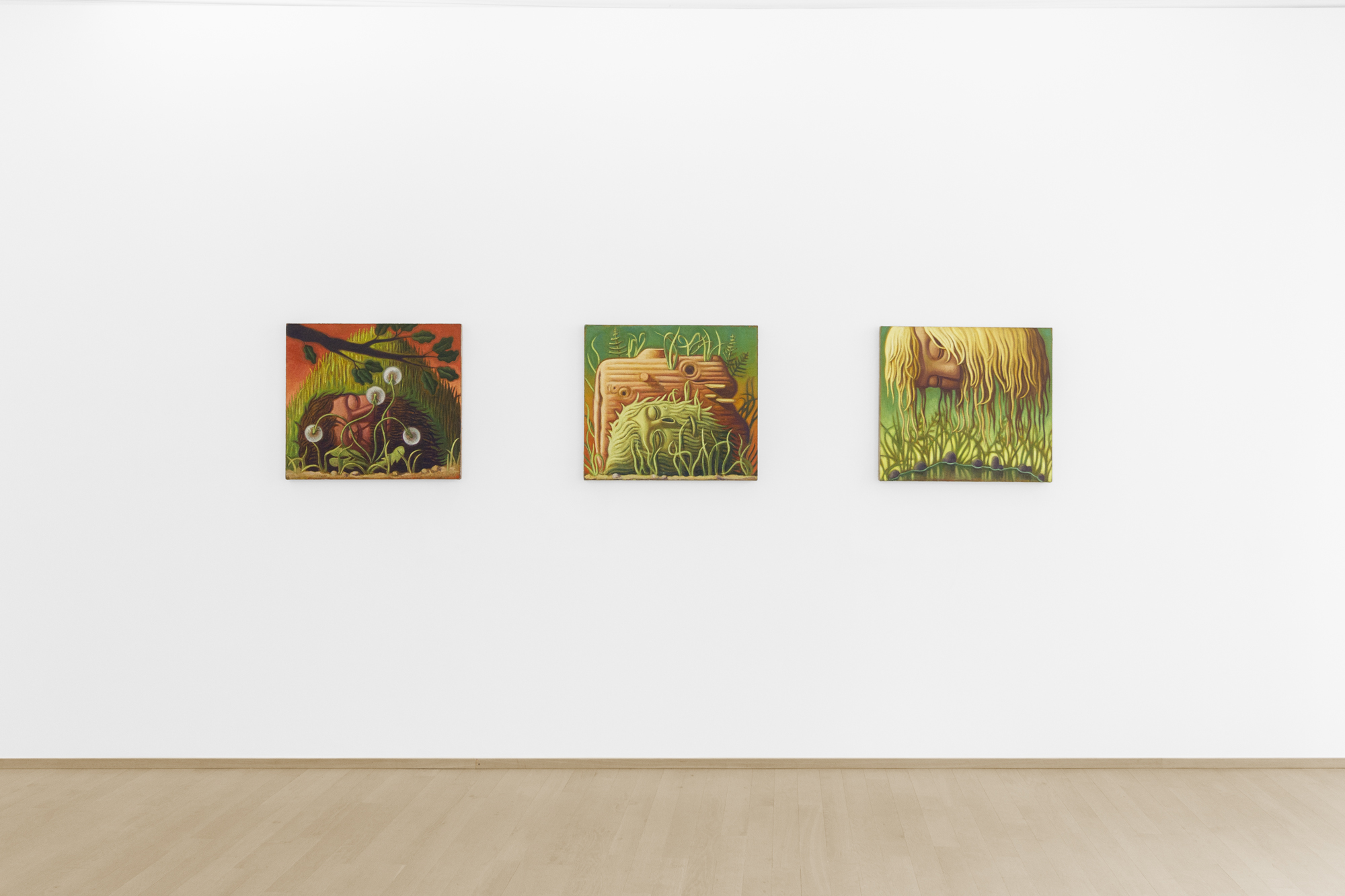

Exhibited Works

Informations

Opening: Thursday 20th June 2024 at 18:00

in the presence of the artist

Nat Meade: Creeper, Sleeper, Weeper

(EN)

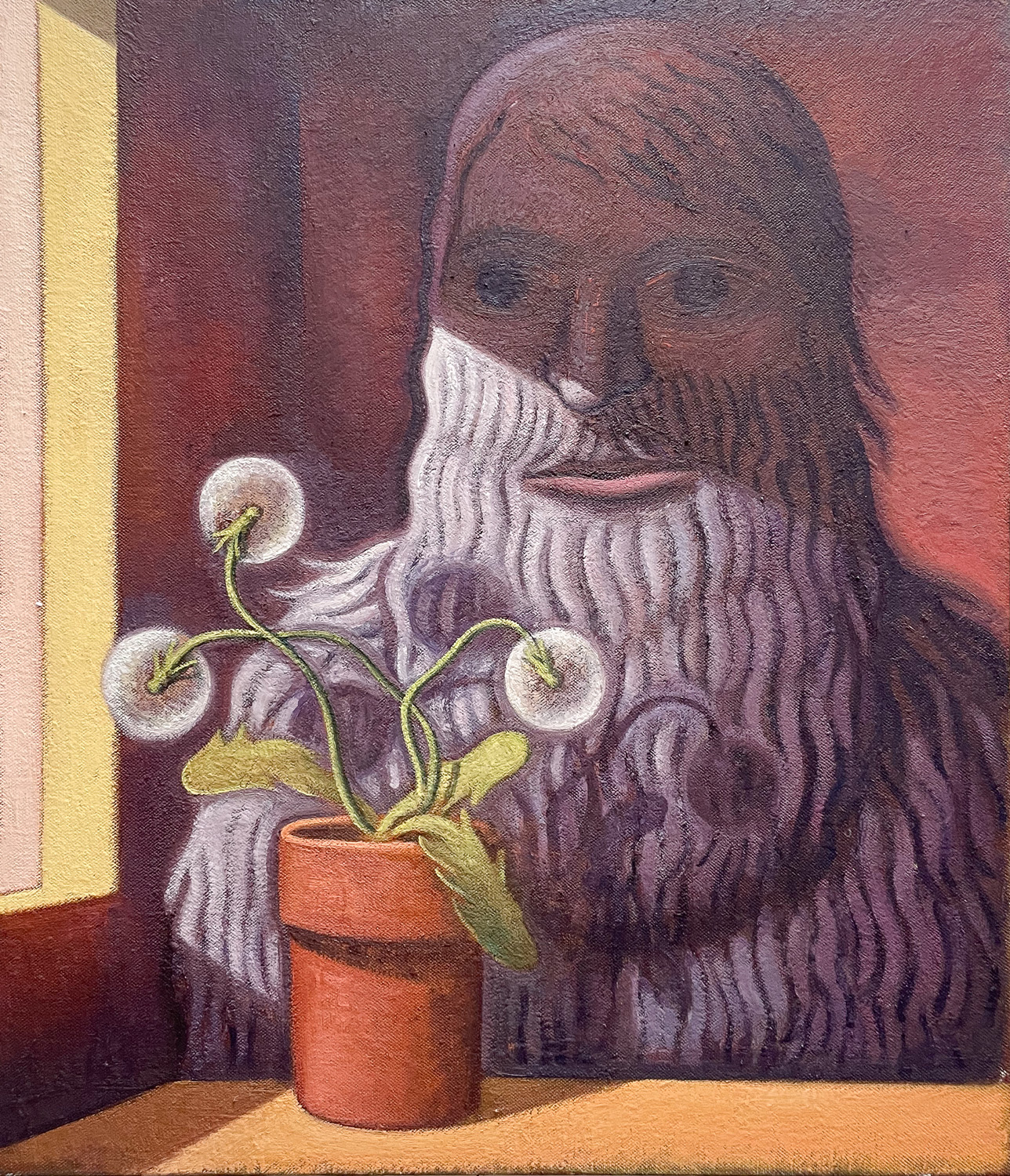

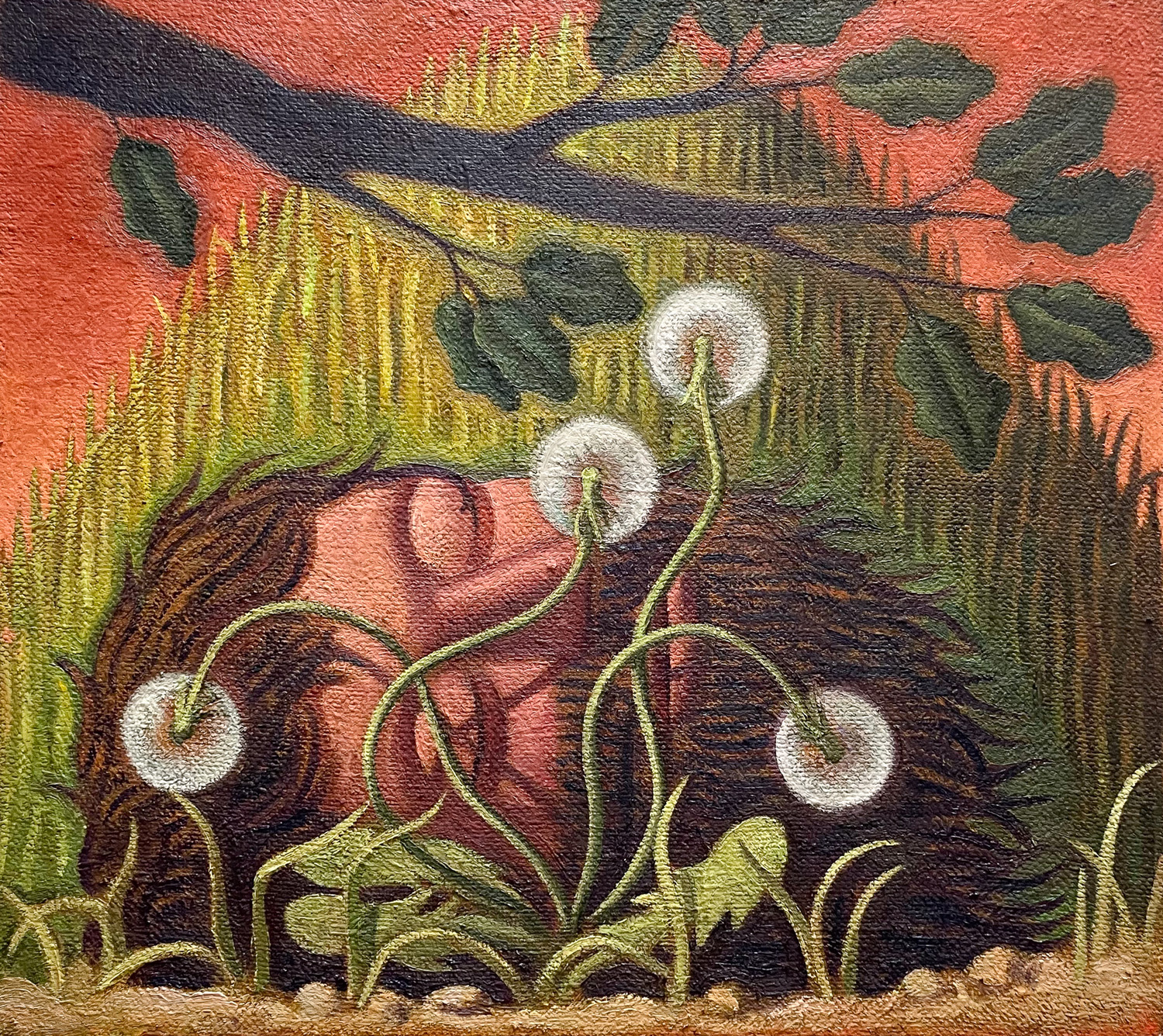

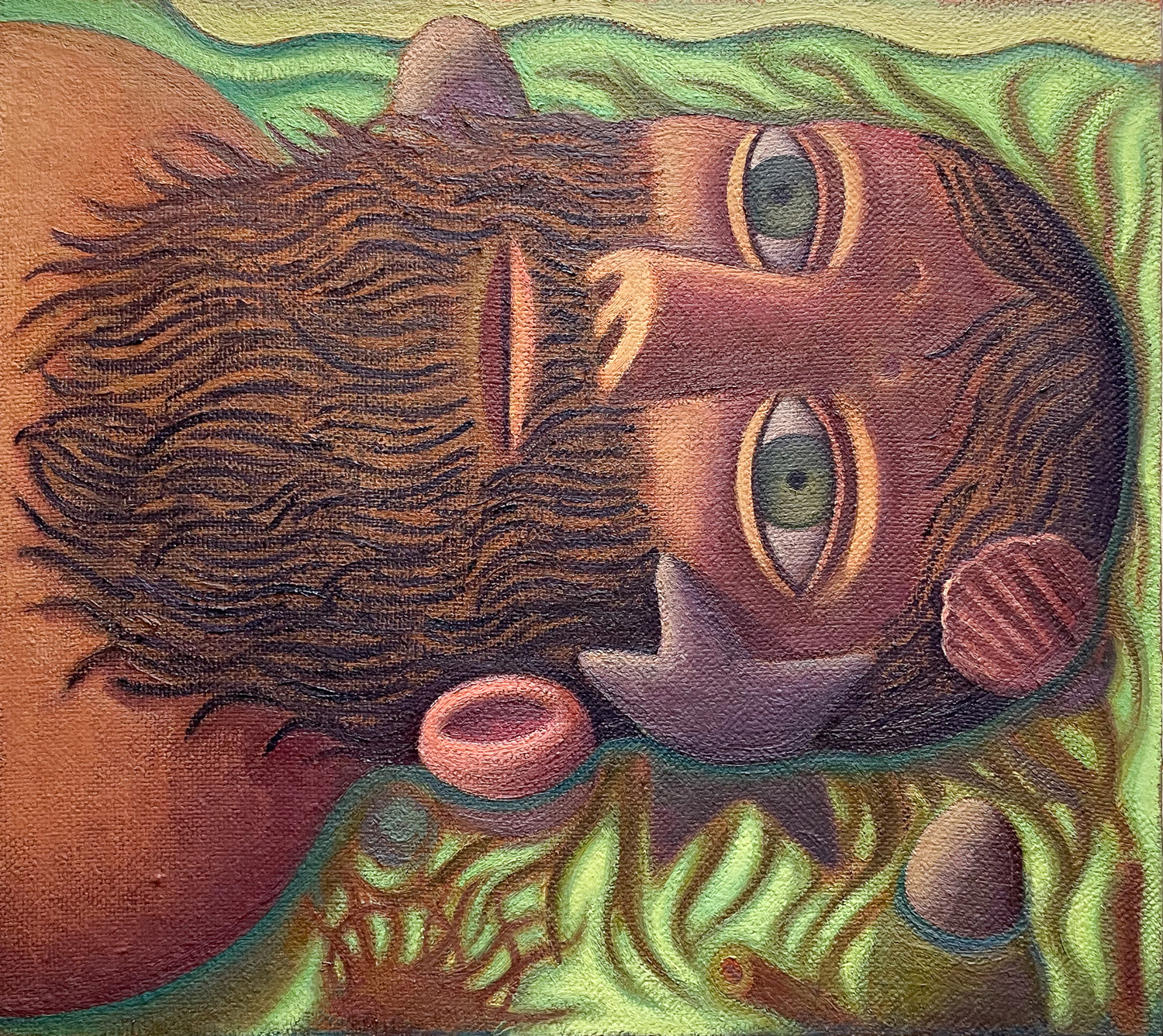

Over the last decade, the American painter Nat Meade has developed a unique style of portraiture within the genre of so-called ‘allegorical autofiction’. In his works, a recurring bearded protagonist embodies emotional states the artist has personally experienced in certain phases of his life or social roles as a man. Their brightly coloured motifs do not refer to external but internal states, while symbolic attributes reinforce the slightly quaint atmosphere that pervades the works.

The archetypal monolithic head, which Meade occasionally depicts in bust length or in pairs or threes within the same painting, harkens back to the artist’s early memory of a woodcut portrait of Walt Whitman (1819–1892) by Antonio Frasconi that hung in his parents’ home — an informal, expressive head with a triangular nose, its full beard rendered by large, thick strokes. Meade, who grew up in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, is well familiar with such rugged physiognomies. In his writings, Whitman, arguably the most famous American poet of the nineteenth century, chastised the upheavals and divisions in modern society, instead romanticising the declining agrarian model and its social cohesion. Even in the twenty-first century, the myths of the founding of the United States and the conquest of the West still inform the country’s understanding of traditional male roles — an outdated cliché, for many reasons. Meade expresses his own unease at this conception through the tongue-in-cheek fatalism of his archaic figures who, despite their robust appearance, seem vulnerable, exhausted, oblivious of the world around them and at times tender, and are often shown sleeping, pondering or crying. Sometimes their detached heads, lying flat on the floor, even transform into objects that tie in with the surrounding natural landscape.

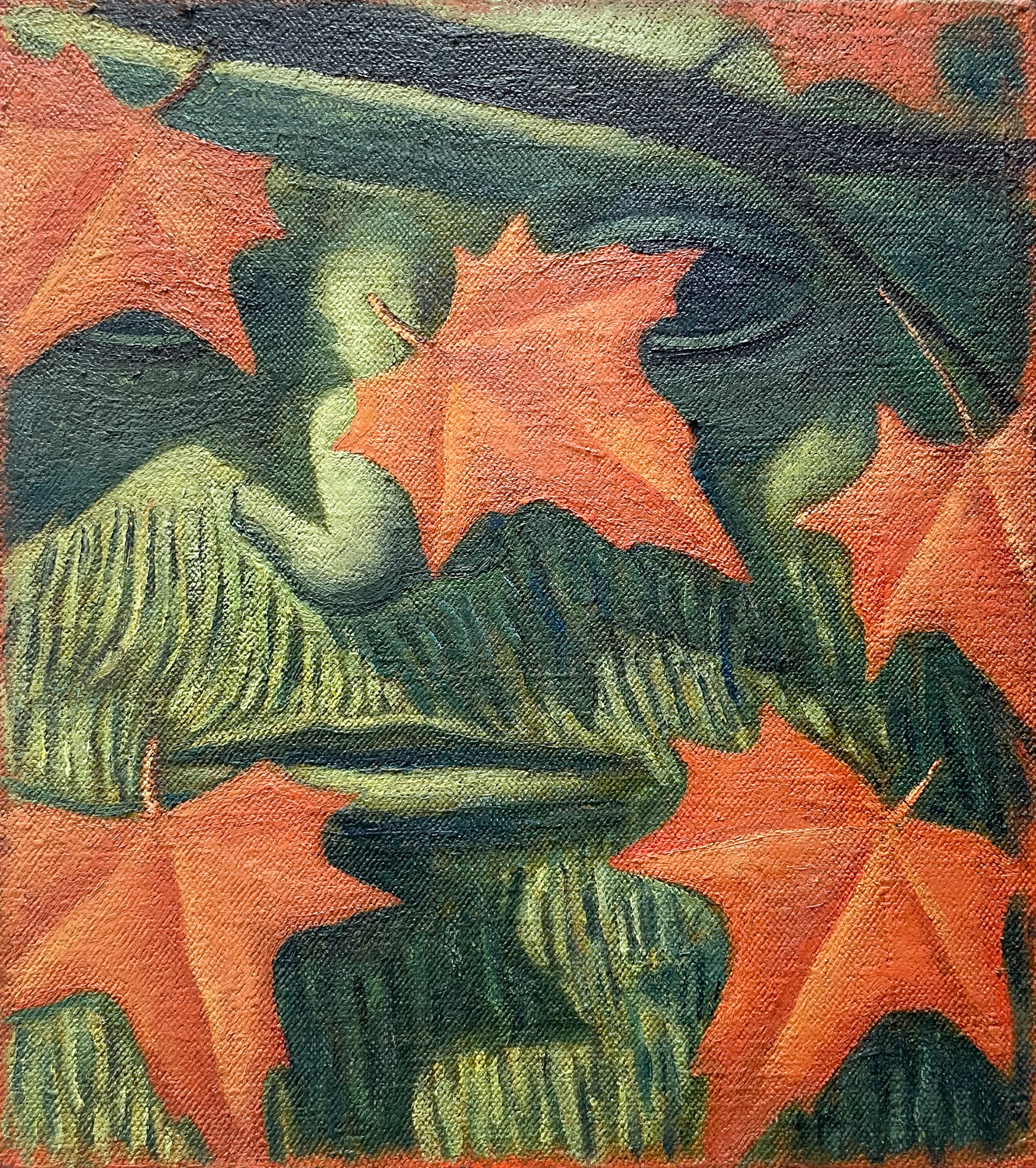

Meade varies the pictorial space by playing with different viewing distances and angles. In his smaller works (such as Basal, Scrim, Canopy), the face appears as if seen through a telephoto lens, filling the entire pictorial space, with even the chin, forehead or cheeks cropped. This leaves no room for peripheral attributes, so that all additions, such as branches with green or autumn-brown leaves, overlap and obscure the face. The relationship between nature and the individual is thus reversed; what we see is not humans who stand or act in nature, but nature that conceals the humans and turns them into a mere backdrop, into something passive.

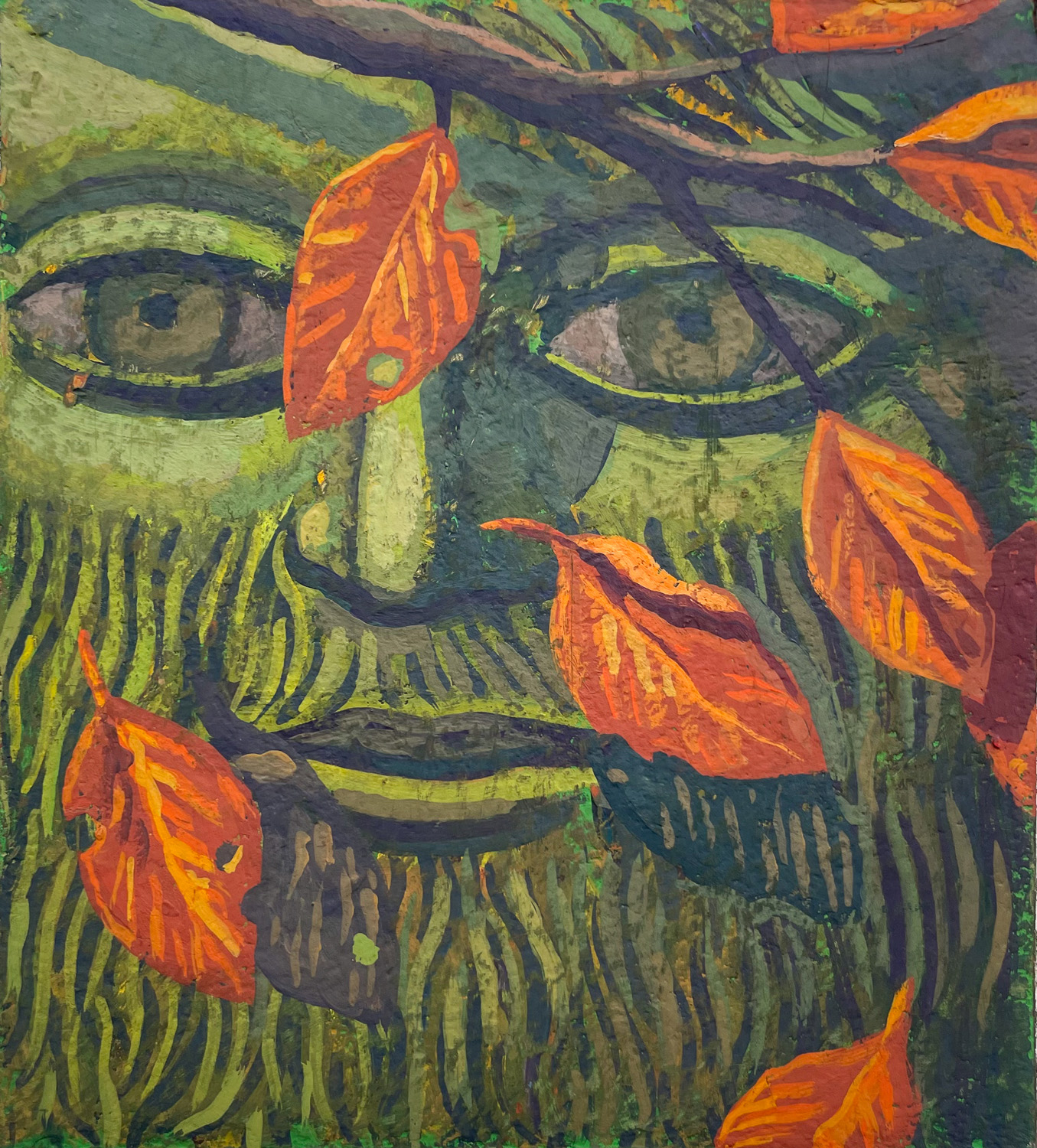

In Meade’s medium-size formats (such as Creeper, Sleeper, Weeper) or the large format Dandylion, the extended angle embraces the surroundings of the person, who is always pictured in the centre ground, leaving space in the background for a hill, a decomposing log or shallow water. The foreground can therefore accommodate (mostly vegetal) elements that are in turn orientated towards the figure, such as dandelion flowers stretching their stems like curious antennae. The prehistoric faces rarely look directly at the viewer — in most cases their eyelids are closed or the pupils are turned thoughtfully to the side. Their mysterious appearance lends them an oracular quality that invites viewers to make them ‘speak’ through their own reflections.

Besides their unusual and subtle, almost burlesque motifs, the colour treatment is a distinctive feature of Meade’s paintings — even his works on paper radiate as if they had built-in backlighting. This effect is achieved through a clever distribution of light in the composition of the motifs: imaginary light sources cast deep shadows on certain objects, while other areas reflect the light and seem to glow from within. In contrast, the surfaces of the paintings are rough and matte — the exact opposite of a high-gloss sheen. The artist uses mainly jute or hemp as canvases, literally slaving away at the harsh texture. Layers of colour are applied but also scraped off again before being reconstructed again, the slow, layered build-up resulting in highly saturated colours. In addition, Meade only uses colour tones that shine in the lighter parts of the painting and transform into radiant dark tones in the shadowy ones: yellow turns to orange or green, pink becomes violet. The weft of the fabric is still clearly visible in the finished picture, creating the impression of a gauze through which we view the strongly lit motif, as though on a theatre stage.

Sabine Dorscheid

(FR)

Au cours des dix dernières années, le peintre américain Nat Meade a développé un type de portrait particulier au sein d’un genre que l’on pourrait qualifier d’ « autofiction allégorique ». Dans ses œuvres, un protagoniste barbu incarne de manière récurrente des émotions que l’artiste a lui-même ressenties à certains moments de sa vie ou dans son rôle social d’homme. Leurs motifs aux couleurs vives renvoient aux sentiments plutôt qu’aux apparences, tandis que des attributs symboliques contribuent à l’atmosphère faussement naïve qui se dégage de ces œuvres.

L’archétype de la tête monolithique, parfois représentée en buste ou par deux ou trois au sein du même tableau, remonte au souvenir d’une gravure dans la maison des parents de l’artiste : un portrait de Walt Whitman (1819-1892) réalisé par Antonio Frasconi. Le poète américain y est représenté sous la forme d’une tête expressive au nez triangulaire, dont la barbe fournie est figurée par des traits larges et épais. Nat Meade, qui a grandi sur la côte nord-ouest des États-Unis, connaît bien ce type de physionomie rude. Dans ses écrits, Whitman, sans doute le poète américain le plus célèbre du XIXe siècle, fustigeait les chamboulements et les divisions de la société moderne, à laquelle il opposait une vision romantisée du modèle agraire évanescent et de sa cohésion sociale. Aujourd’hui encore, les mythes de la fondation des États-Unis et de la conquête de l’Ouest continuent d’infléchir la conception toute masculine des rôles de genre dans le pays – un cliché obsolète à plus d’un titre. L’artiste exprime son propre malaise face à cette situation par le fatalisme légèrement moqueur dont sont empreints ses personnages archaïques qui, malgré leur apparence robuste, semblent vulnérables, épuisés, perdus dans leurs propres rêves, voire tendres, et qu’il représente souvent endormis, pensifs ou en train de pleurer. Parfois leurs têtes détachées, posées à même le sol, se transforment même en objets sculpturaux qui se confondent avec le paysage naturel environnant.

Nat Meade varie l’espace pictural en jouant sur les distances et les angles de vue. Dans ses œuvres plus petites (telles que Basal, Scrim, Canopy), le visage apparaît comme vu à travers un téléobjectif et remplit tout l’espace pictural, le cadrage allant jusqu’à rogner le menton, le front ou les joues. Par manque d’espace, tous les ajouts, telles ces branches aux feuilles vertes ou brunes, viennent alors se superposer sur le visage de manière à l’obscurcir. La relation entre la nature et l’individu est ainsi inversée : ce n’est pas l’humain qui habite ou agit dans la nature, mais la nature qui dissimule l’humain et le transforme en une simple toile de fond, en objet passif.

Dans les formats moyens (tels que Creeper, Sleeper, Weeper) ou le grand format Dandylion, l’angle de vue est élargi de manière à englober l’environnement du protagoniste. Ce dernier est toujours représenté au second plan, permettant à l’arrière-plan d’accueillir une colline, une souche d’arbre en décomposition ou un étang. Le premier plan peut quant à lui accueillir des éléments (essentiellement végétaux), qui sont à leur tour orientés vers le personnage, telles ces fleurs de pissenlit qui semblent étendre leurs tiges comme des antennes. Les visages préhistoriques fixent rarement le spectateur du tableau ; dans la plupart des cas, leurs paupières sont fermées ou les pupilles tournées pensivement sur le côté. Leur apparence mystérieuse leur confère un air d’oracle invitant le spectateur à les faire « parler » à travers leurs propres réflexions.

Outre leurs motifs inhabituels et subtils, voire burlesques, le traitement des couleurs est l’un des traits distinctifs des peintures de Nat Meade, dont même les œuvres sur papier rayonnent comme si elles étaient rétroéclairées. Cet effet est obtenu au moyen d’une répartition judicieuse de la lumière dans la composition des motifs : illuminés par des sources lumineuses fictives, certains objets projettent des ombres marquées, tandis que d’autres zones reflètent la lumière et semblent éclairées de l’intérieur. Les surfaces des peintures sont par contre rugueuses et mates – le contraire même d’une finition brillante. En effet, l’artiste utilise principalement des toiles de jute ou de chanvre, dont il travaille la texture râpeuse en appliquant de nombreuses couches de peinture, qu’il rabote ensuite avant de répéter le processus. Cette lente accumulation de strates de peinture permet d’obtenir des couleurs saturées. Par ailleurs, il prend soin d’utiliser des couleurs qui brillent dans les parties claires du tableau et se transforment en tons sombres rayonnants dans les parties ombragées : le jaune devient orange ou vert, le rose se fait violet. La trame du tissu reste clairement visible dans le tableau fini, créant l’impression d’un voile à travers lequel on observe le motif, éclairé comme sur une scène de théâtre.

Sabine Dorscheid

(DE)

Der US-amerikanische Maler Nat Meade entwickelte über die letzten zehn Jahre eine eigenständige Art von Portraitbildnissen in der Kategorie „Allegorische Autofiktion“. Dabei verkörpert ein stets wiederkehrender bärtiger Protagonist jene Gefühlszustände, die der Künstler selbst in bestimmten Lebensphasen oder sozialen Rollen als Mann durchlebt hat. Seine farbleuchtenden Portraits beziehen sich nicht auf äußere, sondern innere Zustände, zudem verstärken bedeutungsvolle Attribute die wunderlich sprechende Atmosphäre seiner Werke.

Der Typus des holzschnittartigen monolithischen Kopfes, den Meade manchmal auch mit Oberkörper zeigt oder zu zweit oder zu dritt in einem Bild darstellt, geht zurück auf eine frühe Erinnerung des Künstlers an ein Portrait von Walt Whitman (1819–1892), das als Holzschnitt von Antonio Frasconi im elterlichen Haushalt hing: ein informelles, expressives Bildnis mit dreieckiger Nase, dessen großer Vollbart sich in voluminösen Strichen verliert. Nat Meade wuchs an der pazifischen Nordwestküste der Vereinigten Staaten auf und ist mit entsprechend urwüchsigen Physiognomien vertraut. Walt Whitman war der bekannteste amerikanische Lyriker des 19. Jahrhunderts. In seiner Zeit thematisierte er die Umbrüche und Spaltung der Gesellschaft, wobei er im Gegenzug die untergehende agrarische Gesellschaft und deren sozialen Zusammenhalt verklärte. Auch im 21. Jahrhundert flackert der Gründungsmythos der USA und die darauffolgende Westbesiedelung immer noch im amerikanischen maskulinen Rollenverständnis auf. Ein ausgedientes Klischee, aus vielerlei Gründen. Ein Unbehagen, das Meade mit einem augenzwinkernden „Sei’s drum“ in seinen archaischen Figuren repräsentiert, die trotz ihrer robusten Physiognomie verletzlich, erschöpft, selbstvergessen und zuweilen zart wirken; oftmals schlafen, sinnieren oder weinen sie dabei. Manchmal werden ihre losgelösten, umherliegenden Köpfe gar zu Objekten, die sich mit der umgebenden Naturlandschaft verbinden.

Den erfassten Bildraum variiert Meade über unterschiedliche Zoomgrade des Blickwinkels. Bei seinen kleineren Arbeiten (wie Basal, Scrim, Canopy) erscheint das Gesicht wie durch ein Teleobjektiv formatfüllend herangezoomt, sogar Kinn, Stirn oder Wangen werden angeschnitten. Für Attribute ist kein weiterer Umraum vorhanden, so dass die Zugaben dem Gesicht vorgeblendet werden müssen, beispielsweise Zweige mit grünen oder herbstbraunen Blättern. So kehrt sich das Verhältnis von Natur und Person um: Nicht der Mensch steht agierend in der Natur, sondern die Natur verdeckt den Menschen und macht diesen zum Hintergrund, zu etwas Passivem.

Bei den mittleren Formaten (wie Creeper, Sleeper, Weeper) oder dem großen Format (Dandylion) erfasst der erweiterte Blickwinkel auch den Personenumraum. Die Person oder der Kopf befindet sich jeweils im Mittelgrund, so dass im Hintergrund Platz für einen Hügel, einen zerfallenden Baumstumpf oder flaches Wasser bleibt. Im Vordergrund können nun (meist vegetabile) Elemente auftauchen, die sich wiederum auf die Figur ausrichten, etwa Löwenzahnblühten, die ihre Stiele nach dem Protagonisten recken wie neugierige Antennen. Die prähistorisch wirkenden Gesichter schauen den Betrachter nur in Ausnahmenfällen direkt mit ihrem starren Blick an – in den meisten Fällen sind ihre Augenlider geschlossen oder die Pupillen nachdenklich zur Seite gedreht. Die geheimnisvollen Gesichter haben etwas Orakelhaftes und der Betrachter kann sie durch seine eignen Reflexionen zum Sprechen bringen.

Neben den ausgefallenen Motiven, die burlesk und hintersinnig sind, gilt die Farbbehandlung als unverwechselbares Merkmal von Nat Meades Malerei. Seine Leinwände und sogar seine Papierarbeiten strahlen, als hätten sie eine eingebaute Hintergrundbeleuchtung. Diesen Effekt erzielt der Künstler durch die Lichtführung beim Motivaufbau: imaginierte direkte Lichtquellen lassen manche Bildgegenstände satte Schlagschatten werfen, wohingegen andere Partien sehr viel Licht reflektieren und glimmen. Im Widerspruch zu diesem Glimmen stehen die Maloberflächen, die rau und matt sind, das genaue Gegenteil von einem Hochglanzschimmer. Vorzugsweise benutzt der Künstler Jute oder Hanf, an deren Harschheit er sich regelrecht abarbeitet. Viele Farbschichten werden aufgetragen, aber auch wieder abgekratzt, um sie dann wieder neu aufzubauen. Diese Art des langsamen Schichtaufbaus fu?hrt zu einem stark gesättigten Farbausdruck. Zudem verwendet Nat Meade nur Farbtöne, die in den hellen Partien leuchten und sich in den Schattenpartien in strahlende Dunkeltöne verwandeln können. Gelb wird im Schatten zu Orange oder Gru?n, aus Pink wird Violett. Das eigentliche Webmuster der rauen Stoffe ist auch beim fertigen Bild noch gut abzulesen, so dass der Eindruck entsteht, es könne ein Gazestoff sein, der das dahinterliegende Motiv nur durch die starke Beleuchtung sichtbar mache, wie auf einer Theaterbu?hne.

Sabine Dorscheid

Translations (original text in German): Patrick (Boris) Kremer

Photo credits: © Audrey Jonchères | Nosbaum Reding